Wisconsin Supreme Court declines request to determine maps for recall and special elections4/3/2024 The Wisconsin Supreme this morning denied a motion by the Wisconsin Elections Commission seeking clarification on what maps apply to recall and special elections.

The court issued the order in the Clarke redistricting case. The court stated in the order that “(o)n December 22, 2023, we enjoined the ‘Elections Commission from using [the prior] legislative maps in all future elections’ because the maps violated the Wisconsin Constitution.” The Legislature then passed redistricting maps proposed by Gov. Tony Evers. On Feb. 19, 2024, Evers signed them into law as 2023 Wisconsin Act 94. Act 94 states that the new maps go into effect for seats up in the 2024 fall general election, leaving a question about what maps apply between now and then for special and recall elections. The old maps are unconstitutional, but do the new maps apply yet? The Legislature has ended its session so a legislative clarification looks unlikely. The general election is on Nov. 5, 2024, with a primary on Aug. 13, 2024. A special election is due for Senate District 4. The seat is vacant after Sen. Lena Taylor resigned her seat to become a Milwaukee County Circuit Court judge. Meanwhile, a second effort to recall Rep. Robin Vos (R-Rochester) is underway. The court said that weighing in on what maps apply to special and recall elections would be an impermissible advisory opinion. “Act 94 is not before us in the Clarke case and any examination of these maps departs from the relief requested in Clarke v. WEC,” the court wrote. The court said it would not "make a pronouncement based on hypothetical facts," adding that the Wisconsin Elections Commission bears statutory responsibility for administering elections.

0 Comments

Wisconsin Justice Initiative recently asked the Wisconsin Supreme Court, director of state courts, and members of the State Capitol and Executive Residence Board (SCERB), to display new artwork in the State Capitol courtroom to reflect diversity in the judiciary, bar, and public. SCERB is the state board that controls renovations and installations of fixtures, decorative items, and furnishings in the Capitol building. The Wisconsin Constitution and opinions of the Wisconsin Supreme Court apply to all Wisconsinites and shape the state's legal system and citizens’ rights. Yet the chamber in which the Supreme Court sits to interpret the state’s constitution and statutes reflects an outdated world that fails to include more than half of Wisconsin's population. None of the courtroom’s murals includes a woman, and the only people of color are defendants in a murder trial and some possibly mixed-race men as jurors. Of note, in that murder trial the judge's decision was based on his belief that the primary defendant, Chief Oshkosh, was not “an intelligent conscious being" under the law. All of the portraits and busts in the courtroom’s vestibule are of white men. This year marks the 150th anniversary of admission of the first woman, Lavinia Goodell, to law practice in Wisconsin. In its letters to SCERB and the court, WJI urged them to recognize the anniversary by adding to the vestibule walls portraits of the court’s female chief justices — Shirley Abrahamson, Patience Roggensack, and Annette Ziegler. WJI also asked SCERB and the court to commission two new busts for the vestibule or hearing room: one of a woman and one of a person of color. WJI suggested Goodell and William T. Green. Green was the first Black lawyer in Milwaukee and fought for civil rights through legislation, court cases, and community organizing. WJI published blog articles about Goodell and Green as part of its “Unsung Heroes” series about women and people of color who contributed to Wisconsin legal history but whose stories have not adequately been heard and acknowledged. Supreme Court hearing room murals and vestibule. Photographs by Margo Kirchner.

Note: We are crunching Supreme Court of Wisconsin decisions down to size. The general rule for WJI's "SCOW docket" posts is that no justice gets more than 10 paragraphs as written in the actual decision, and all parts of the decision (majority, concurrences, dissents) are contained in one post. This one is a little different, though. This time, with this case, we are doing it in three parts: first the majority decision, then the longest dissent, then the remaining two dissents. Why? Because this package of writings is extremely important: redistricting of the Legislature. In addition, the opinions are extremely long—229 pages in all. Due to the size of the opinions, we are giving the majority opinion writer 18 paragraphs and each other opinion writer up to 15. Other than that, the rules remain the same. The "upshot" and "background" sections do not count as part of the paragraph restrictions because of their summary and very necessary nature. We've removed citations from the opinion for ease of reading (except, in this particular case, regarding some dictionary definitions), but may link to important cases cited or information about them. Italics indicate WJI insertions except for case names and emphasis added by the opinion writer, all of which also are italicized. Read part 1 (majority opinion) and part 2 (Ziegler dissent). The case: Rebecca Clarke v. Wisconsin Elections Commission Majority: Justice Jill J. Karofsky (51 pages), joined by Justices Ann Walsh Bradley, Rebecca Dallet, and Janet Protasiewicz Dissents: Chief Justice Annette Kingsland Ziegler (89 pages), Justice Rebecca Grassl Bradley (56 pages plus an appendix of 11 pages), and Justice Brian Hagedorn (22 pages)  Grassl Bradley dissent Riding a Trojan horse named Contiguity, the majority breaches the lines of demarcation separating the judiciary from the political branches in order to transfer power from one political party to another. Alexander Hamilton forewarned us that "liberty can have nothing to fear from the judiciary alone, but would have everything to fear from its union with either of the other departments." With its first opinion as an openly progressive faction, the members of the majority shed their robes, usurp the prerogatives of the legislature, and deliver the spoils to their preferred political party. These handmaidens of the Democratic Party trample the rule of law, dishonor the institution of the judiciary, and undermine democracy. The outcome in this case was preordained with the April 2023 election of a candidate who ran on a platform of "taking a fresh look" at the "rigged" maps. As promised just two days after Protasiewicz's election, petitioners filed this case only one day after she joined the court. The majority chooses contiguity as a convenient conduit by which to toss the legislative maps adopted by this court in 2022 as a remedy for malapportionment, but any issue grounded in state law would suffice in order to insulate the majority's activism from review by the United States Supreme Court. The majority's machinations do not shield it from the Court vindicating the respondents' due process rights, however. Litigants are constitutionally entitled to have their cases heard by a fair and impartial tribunal, an issue of primary importance the majority absurdly dismisses as "underdeveloped." The parties fully briefed the due process claim, which Protasiewicz unilaterally rejected. While this court is powerless to override her recusal decision, the United States Supreme Court is not. The majority's treatment of the remaining issue sophomorically parrots the petitioners' briefing and undermines the rule of law. The Wisconsin Constitution requires assembly districts "to consist of contiguous territory" and senate districts "of convenient contiguous territory." For fifty years, maps drawn by both Republican and Democratic legislative majorities contained districts with detached territory. State and federal courts uniformly declared such districts to be "legally contiguous even if the area around the island is part of a different district." Just last year, three members of the majority in this very case adopted maps containing districts with detached territory. This well-established legal conclusion having become politically inconvenient, the same three justices now deem the existence of such districts "striking." If this creative constitutional "problem" were so glaringly obvious, then the attorneys who neglected to raise the issue over the last five decades committed malpractice, and the federal and state judges who adopted maps with districts containing detached territory should resign for incompetency. No one is fooled, however. The members of the majority refashion the law to achieve their political agenda. The precedent they set (if anything remains of the principle) devastates the rule of law. The Wisconsin Constitution commands redistricting to occur once every ten years. Both state and federal courts have always respected "the command in the Wisconsin Constitution not to redistrict more than once each 10 years." The majority's machinations in this case open the door to redistricting every time court membership changes. A supreme court election in 2025 could mean Clarke (this case) is overturned, Johnson (the court’s prior redistricting case, with three decisions known as Johnson I, Johnson II, and Johnson III) is restored, and new maps adopted. In 2026 or 2027, Johnson could be overturned (again), Clarke resurrected, and new maps adopted. This cycle could repeat itself in 2028. And in 2029. And in 2030. *** Upon completion of the 2020 census, the governor vetoed the redistricting plans passed by the legislature, so the court in Johnson enjoined the 2011 legislative maps that had become unconstitutionally malapportioned due to population shifts. Political impasse left the judiciary as the only branch able to act. There is absolutely no precedent for a supreme court to enjoin its own remedy one year later. Perhaps if the majority focused on studying the law rather than rushing to set its political machinations on a ridiculous fast track, it would avoid such embarrassing errors. *** Every party in Johnson stipulated before we decided Johnson I that the contiguity requirements under Article IV, Sections 4 and 5 of the Wisconsin Constitution permit municipal islands detached from their assigned districts. We agreed. So did the dissenters. Every party—including the Governor—submitted maps containing municipal islands. A majority in Johnson II, selected the Governor's proposed legislative maps, municipal islands and all; three justices in this current majority blessed those maps as constitutional. *** After the court decided Johnson I, the Governor, or any other petitioner who participated in the case, could have filed a motion for reconsideration on contiguity, asking the court to correct the allegedly flagrant constitutional error somehow repeatedly overlooked by countless lawyers, federal judges, and justices of this court for five decades. To no one's surprise, they instead waited for the Clarke petitioners to file this suit immediately after the makeup of the court changed, courtesy of an election bought and paid for by the Democratic Party of Wisconsin. *** Grassl Bradley then discusses how the majority misused dictionary definitions regarding the meaning of “contiguous.” The majority does not seem to recognize the limits of dictionaries, or the importance of acknowledging and weighing different definitions. The majority resorts to fabrication with its obviously false claim that all dictionaries define the term "contiguous" the way the majority prefers. The remarkable power to declare something unconstitutional—and forever remove it from democratic decision making—should be exercised carefully and with humility. The majority's drive-by dictionary citations exhibit a slipshod analysis. *** If the current maps were unconstitutional, the only proper exercise of this court's power would be a remedy that respects the legislature's and the governor's constitutionally prescribed roles in the redistricting process. If the members of the majority were acting as a court rather than a super legislature of four, they would modify the maps only to the extent necessary to comply with the law. Specifically, if the majority wished to remedy only detached municipal islands, as it professes, it would adopt the respondents' proposal and redraw only those districts containing detached territory. The majority refuses to do so, with nothing more than a single sentence explanation in which the majority says a more modest remedy would "cause a ripple effect across other areas of the state" so new maps are "necessary." The majority offers zero support for this conclusory assertion because none exists. The majority instead dispenses with the existing maps in order to confer an advantage on its preferred political party with new ones. *** The majority abandons the court's least-change approach adopted in Johnson I in order to fashion legislative maps that "intrude upon the constitutional prerogatives of the political branches and unsettle the constitutional allocation of power." The least-change approach in Johnson I guaranteed the court would ground any reapportionment decisions in the law alone, leaving the political decisions of redistricting to the political branches where they belong. The majority's decision to discard the judicially restrained methodology of Johnson I unveils its motivation to redraw the legislative maps for the benefit of Democratic state legislative candidates. By design, the majority's transparently political approach will reallocate political power in Wisconsin via a draconian remedy, under the guise of a constitutional "error" easily rectified by modest modifications to existing maps. *** As the respondents proposed, any contiguity violation could be remedied by simply dissolving municipal islands into their surrounding assembly districts. The majority dismisses the idea without explaining why the maps must instead be redrawn in their entirety. To say the quiet part out loud, confining the court's remedy to districts with municipal islands would deprive the majority of its desired political outcome. Its overreach flouts not only Johnson I but also black-letter law limiting the judiciary's remedial powers. *** Buried at the end of its opinion, the majority identifies "partisan impact" as the fifth and last "redistricting principle" it will consider in reallocating political power in this state. Its placement disguises the primacy this factor will have in the majority's schemes. The majority neglects to offer a single measure, metric, standard, or criterion by which it will gauge "partisan impact." Most convenient for the majority's endgame, there aren't any, lending the majority unfettered license to design remedial maps fulfilling the majority's purely political objectives. In considering "partisan impact," the majority acts without authority. Unlike other state constitutions, "[n]othing in the Wisconsin Constitution authorizes this court to recast itself as a redistricting commission in order 'to make [its] own political judgment about how much representation particular political parties deserve——based on the votes of their supporters——and to rearrange the challenged districts to achieve that end.'" "The people have never consented to the Wisconsin judiciary deciding what constitutes a 'fair' partisan divide; seizing such power would encroach on the constitutional prerogatives of the political branches." *** Redistricting is the quintessential "political thicket." We should not decide such cases unless, as in 2021, we must. In this case, we need not enter the thicket. Unlike the majority, I would not address the merits. A collateral attack on a supreme court judgment, disguised as an original action petition, would ordinarily be dismissed upon arrival. Allowing petitioners' stale claims to proceed makes a mockery of our judicial system, politicizes the court, and incentivizes litigants to sit on manufactured redistricting claims in the hopes that a later, more favorable makeup of the court will accept their arguments. The doctrines of laches and judicial estoppel exist to prevent such manipulation of the judicial system.  Hagedorn dissent No matter how today's decision is sold, it can be boiled down to this: the court finds the tenuous legal hook it was looking for to achieve its ultimate goal—the redistribution of political power in Wisconsin. Call it "promoting democracy" or "ending gerrymandering" if you'd like; but this is good, old-fashioned power politics. The court puts its thumb on the scale for one political party over another because four members of the court believe the policy choices made in the last redistricting law were harmful and must be undone. This decision is not the product of neutral, principled judging. The matter of legislative redistricting was thoroughly litigated and resolved after the 2020 census. We adopted a judicial remedy (new maps) and ordered that future elections be conducted using these maps until the legislature and governor enact new ones. That remedy remains in place, and under Wisconsin law, is final. Now various parties, new and old, want a mulligan. But litigation doesn't work that way. Were this case about almost any other legal matter, the answer would be cut-and-dried. We would unanimously dismiss the case and reject this impermissible collateral attack on a prior, final decision. So why are the ordinary methods of deciding cases now thrown by the wayside? Because a majority of the court imagines it has some moral authority, dignified by a black robe, to create "fair maps" through judicial decree. To be sure, one can in good faith disagree with Johnson's holding that adhering as closely as possible to the last maps enacted into law—an approach called "least change"—is the most appropriate use of our remedial powers. And the claim here that the constitution's original meaning requires the territory in all legislative districts to be physically contiguous is probably correct, notwithstanding decades of nearly unquestioned practice otherwise. But that does not give litigants a license to ignore procedure and initiate a new case to try arguments they had every opportunity to raise in the last action, but did not. Procedural rules exist for a reason, and we should follow them. As we have previously explained, "Litigation rules and processes matter to the rule of law just as much as rendering ultimate decisions based on the law. Ignoring the former to reach the latter portends of favoritism to certain litigants and outcomes." Indeed it does. The majority heralds a new approach to judicial decision-making. It abandons prior-stated principles regarding finality in litigation, standing, stare decisis, and other normal restraints on judicial will—all in favor of expediency. But principles adopted when convenient, and ignored when inconvenient, are not principles at all. It is precisely when one's principles are tested and costly—yet are kept nonetheless—that they prove themselves truly held. The unvarnished truth is that four of my colleagues deeply dislike maps that give Republicans what they view as an inappropriate partisan advantage. Alas, when certain desired results are in reach, fidelity to prior ideals now seems . . . a bit less important than before. No matter how pressing the problem may seem, that is no excuse for abandoning the rules of judicial process that make this institution a court of law. The majority's outcome-focused decision-making in this case will delight many. A whole cottage industry of lawyers, academics, and public policy groups searching for some way to police partisan gerrymandering will celebrate. My colleagues will be saluted by the media, honored by the professoriate, and cheered by political activists. But after the merriment subsides, the sober reality will set in. Without legislative resolution, Wisconsin Supreme Court races will be a perpetual contest between political forces in search of political power, who now know that four members of this court have assumed the authority to bestow it. A court that has long been accused of partisanship will now be enmeshed in it, with no end in sight. Rather than keep our role in redistricting narrow and circumspect, the majority seizes vast new powers for itself. We can only hope that this once great court will see better days in the future. I respectfully dissent. *** (T)he majority falls woefully short in supporting its conclusion that the parties met the requirements for standing. "Standing is the foundational principle that those who seek to invoke the court's power to remedy a wrong must face a harm which can be remedied by the exercise of judicial power." Courts do not have the power to "weigh in on issues whenever the respective members of the bench find it desirable." As three members of today's majority have previously opined, "standing is important . . . because it reins in unbridled attempts to go beyond the circumscribed boundaries that define the proper role of courts." *** The Governor's legal positions throughout this redistricting litigation saga are astonishing; any other litigant in any other lawsuit would be promptly dismissed from the case. In Johnson, the Governor initially argued that the constitution's contiguity requirement mandated physical contiguity, just like the petitioners argue in this case. Then, the Governor changed course and agreed with all the other parties that keeping municipalities together did not violate the contiguity requirement. We agreed and so held, and invited map proposals consistent with our decision. The Governor then submitted proposed remedial maps with municipal islands—the very thing the Governor now argues violates the constitution! And in briefing regarding the other map proposals, which also contained municipal islands, the Governor never questioned their legality—even though he was invited to address any and all legal deficiencies in those proposals. *** The Governor's flip-flopping is classic claim preclusion. The Governor came before this court to litigate how to remedy malapportionment; argued that contiguity permits municipal islands; submitted maps (that this court initially adopted) containing dozens of municipal islands; and now, in a subsequent action, complains that this court's remedy violated the constitution because its map contained municipal islands. This argument was litigated in Johnson. And even if it wasn't, it obviously could have been litigated. If the legislature's proposed maps that we ultimately adopted violated the contiguity requirements, the Governor could have said so. He did not; no one did. The Governor is barred by claim preclusion from litigating the issues before us again. *** Given this, I do not see how the court can bypass the voter standing problems by relying on the Governor's purported authority to challenge a districting plan. Even if the Governor has standing to litigate on behalf of Wisconsinites to ensure a districting plan complies with the constitution, this does not end the matter. The question the majority must answer—but does not—is whether the Governor has the right to litigate on behalf of Wisconsin voters over and over again, taking different positions each time, until he gets the result he wants. The ordinary application of claim preclusion prohibits the Governor from relitigating the issues he either raised or could have raised during the last litigation. The majority's standing decision—resting on a party that should be dismissed——once again looks like an outcome in search of a theory. Next, the majority ignores the impropriety of the court issuing an injunction on our own injunction. The majority enjoins the Wisconsin Elections Commission from using the legislative maps that we, just 20 months ago, mandated they use. I've never seen anything quite like it. The general rule is that judgments—and injunctions along with them—are final and, absent fraud, cannot be collaterally attacked. This case is exactly that—an impermissible collateral attack on a prior, final case. The majority's response is that courts regularly modify prior injunctions in redistricting cases without reopening old cases. This is true, but only because there is an intervening event every ten years: the U.S. Census. And following completion of the census, the constitution requires that population shifts be accounted for afresh. So when courts issue a new injunction in new redistricting cases, they do so because the law provides that every districting plan, whether adopted by a court or the legislature, must be updated following the census. That is not the case here. *** (T)he majority says "partisan impact" will guide its decision in selecting new remedial maps. But what does this mean? Should the maps maximize the number of competitive districts? Should the maps seek to achieve something close to proportionate representation? Should the maps pick some reasonable number of acceptable Republican and Democratic-leaning seats in each legislative chamber? I have no idea, and neither do the parties. The court nonetheless invites the submission of maps motivated by partisan goals, just as the petitioners hoped. And with a certain amount of gusto, the majority insists it is being neutral by openly seeking maps aimed at tilting the partisan balance in the legislature. The court announces it does not have "free license to enact maps that privilege one political party over another," all the while obliging the wishes of litigants who openly seek to privilege one political party over another. The irony could not be any thicker. The court does not provide any meaningful guidance to the parties on how to satisfy its "political impact" criteria. No standards, no metrics, nothing. Instead, it appears the majority wishes to hide behind two "consultants" who will make recommendations on which maps are preferable. Those consultants will presumably use some standards to make this kind of judgment,14 but the majority will not permit them to be subject to discovery or witness examination.15 Like the great and powerful Oz, our consultants will dispense wisdom without allowing the parties to see and question what is really behind the curtain. And at the end of this, the consultants will offer options from which the court can choose. This attempt at insulating the court from being transparent about its decisional process is hiding in plain sight. The court also fails to interact with the constitutional requirement that districts "be bounded by county, precinct, town or ward lines." Currently, districts that are not physically contiguous are that way because the legislature (and courts) have attempted to comply with the requirement that counties, towns, and wards not be split—thus, keeping municipal islands in the same legislative district as the rest of the municipality. The court now determines that strict compliance with contiguity is required, but it ignores how that may be in tension with the equally required constitutional command to keep county, town, and ward lines sacrosanct. While absolute compliance with the "bounded by" clause is impossible given the one-person, one-vote decisions of the United States Supreme Court, a return to a more exacting constitutional standard would likely prohibit running districts across county lines, or breaking up towns or wards (of which municipalities are composed) unless necessary to comply with Supreme Court precedent. This could conflict with strict physical contiguity. *** Although this litigation is not yet over, it is clear to me that the Wisconsin Supreme Court is not well equipped to undertake redistricting cases without a set of rules governing the process. In (a prior case), this court recognized the need for special procedures governing future redistricting cases. We received a rule petition seeking to do exactly that prior to Johnson, but this court could not come to an agreement about what such a process would look like or whether we should have one. I believed then, and am now fully convinced, that some formalized process is desperately needed before we are asked to do this again. Note: We are crunching Supreme Court of Wisconsin decisions down to size. The general rule for WJI's "SCOW docket" posts is that no justice gets more than 10 paragraphs as written in the actual decision, and all parts of the decision (majority, concurrences, dissents) are contained in one post. . This one is a little different, though. This time, with this case, we are doing it in three parts: first the majority decision, then the longest dissent, then the remaining two dissents. Why? Because this package of writings is extremely important: redistricting of the Legislature. In addition, the opinions are extremely long—229 pages in all. Due to the size of the opinions, we are giving the majority opinion writer 18 paragraphs and each other opinion writer up to 15. Other than that, the rules remain the same. The "upshot" and "background" sections do not count as part of the paragraph restrictions because of their summary and very necessary nature. We've removed citations from the opinion for ease of reading (except, in this particular case, regarding some dictionary definitions), but may link to important cases cited or information about them. Italics indicate WJI insertions except for case names and emphasis added by the opinion writer, all of which also are italicized. The case: Rebecca Clarke v. Wisconsin Elections Commission Majority: Justice Jill J. Karofsky (51 pages), joined by Justices Ann Walsh Bradley, Rebecca Dallet, and Janet Protasiewicz Dissents: Chief Justice Annette Kingsland Ziegler (89 pages), Justice Rebecca Grassl Bradley (56 pages plus an appendix of 11 pages), and Justice Brian Hagedorn (22 pages)  Ziegler Ziegler The Ziegler dissent This deal was sealed on election night. Four justices remap Wisconsin even though this constitutional responsibility is to occur every ten years, after a census, by the other two branches of government. The public understands this. Nonetheless, four justices impose their will on the entire Assembly and half of the Senate, all of whom are up for election in 2024. Almost every legislator in the state will need to respond, with lightning speed, to the newly minted maps, deciding if they can or want to run, and scrambling to find new candidates for new districts. All of this remains unknown until the court of four, and its hired "consultants," reveal the answer. The parties' dilatory behavior in bringing this suit at this time should not be rewarded by the court's granting of such an extreme remedy, along such a constrained timeline. Big change is ahead. The new majority seems to assume that their job is to remedy "rigged" maps which cause an "inability to achieve a Democratic majority in the state legislature." These departures from the judicial role are terribly dangerous to our constitutional, judicial framework. No longer is the judicial branch the least dangerous in Wisconsin. Redistricting was just decided by this court in the Johnson litigation (the court’s redistricting litigation in 2021 and 2022). This court was saddled with the responsibility to adopt maps because the legislative and executive branches were at an impasse, and absent court action, there would be a constitutional crisis. As a result of Johnson, there are census-responsive maps in place. Nonetheless, the four robe-wearers grab power and fast-track this partisan call to remap Wisconsin. Giving preferential treatment to a case that should have been denied, smacks of judicial activism on steroids. The court of four takes a wrecking ball to the law, making no room, nor having any need, for longstanding practices, procedures, traditions, the law, or even their co-equal fellow branches of government. Their activism damages the judiciary as a whole. Regrettably, I must dissent. The court of four's outcome-based, end-justifies-the-means judicial activist approach conflates the balance of governmental power the people separated into three separate branches, to but one: the judiciary. Such power-hungry activism is dangerous to our constitutional framework and undermines the judiciary. When four members of this court "throw off constraints, revise the rules of decision, and set the law on a new course," it is prudent for all of us to "question whether that power has been exercised judiciously" or whether it is instead an exercise in judicial activism. Today is the latest in a series of power grabs by this new rogue court of four, creating a pattern of illicit power aggregation which disrupts, if not destroys, stability in the law. *** Unfortunately, this latest unlawful power grab is not an outlier, but is further evidence of a bold, agenda-driven pattern of conduct. To set the stage, recall that these four members of the court came out swinging, when they secretly and unilaterally planned and dispensed with court practices, procedures, traditions, and norms. Preordained and planned even before day one of the new justice's term on August 1, 2023, but unknown to the other members of the court, the four acted to aggregate power, meeting in secret as a "super-legislature." They met behind closed doors, at a rogue, unscheduled and illegitimate meeting, over the protestations of their colleagues, in violation of longstanding court rules and procedures. Even before day one of the newest justice's term, and before the court term started in September, they met, in secret, to carry out their plan, only known to them, to dispense with over 40 years of court-defined precedent. They even took the unprecedented action to strip the constitutional power of the chief justice, which had been understood for decades of chief justices and different court membership, instead usurping that role through an administrative committee. For nearly four decades and five chief justices, every member of the court had respected the power the people of Wisconsin constitutionally vested in the chief justice to administrate the court system. *** (J)ust last year in Johnson, the court determined, and all agreed, that the maps complied with the contiguity requirement. "Contiguity for state assembly districts is satisfied when a district boundary follows the municipal boundaries. Municipal 'islands' are legally contiguous with the municipality to which the 'island' belongs." Even the parties now arguing that the maps are not contiguous recognize that the contiguity requirement has been deemed satisfied not only in the maps the parties submitted in the Johnson litigation, but also in the maps the state has relied on for the last 60 to 70 years. Moreover, every person who wished to have a say or participate in the Johnson litigation was welcome to do so and did. No one sought reconsideration of the Johnson litigation while it was within their power to do so. Johnson went all the way to the United States Supreme Court and back. Some of the litigants now were part of the Johnson litigation, some chose not to engage. But the law imposes consequences for those who choose to sit out of litigation entirely, and for those who stipulate to or do not make an argument in litigation. Finality of litigation does not endow one with the authority to wait to see what happens in that litigation cycle, forego timely filing a motion for reconsideration, and then bring arguments years after the fact, with the only intervening change being the court's composition. Four members of this court choose to not let pesky parameters like finality or other foundational judicial principles, or even the constitution, stand in the way of the predetermined political outcome which they seem preordained to deliver. Given the new court of four's conduct so far, we can expect more such judicial mischief in the future. On their watch, Wisconsin is poised to become a litigation nightmare. What is next? *** (T)his original action is wrongly taken and decided for a host of heretofore understood and respected legally-binding tenets. However, the court of four glosses right over them.

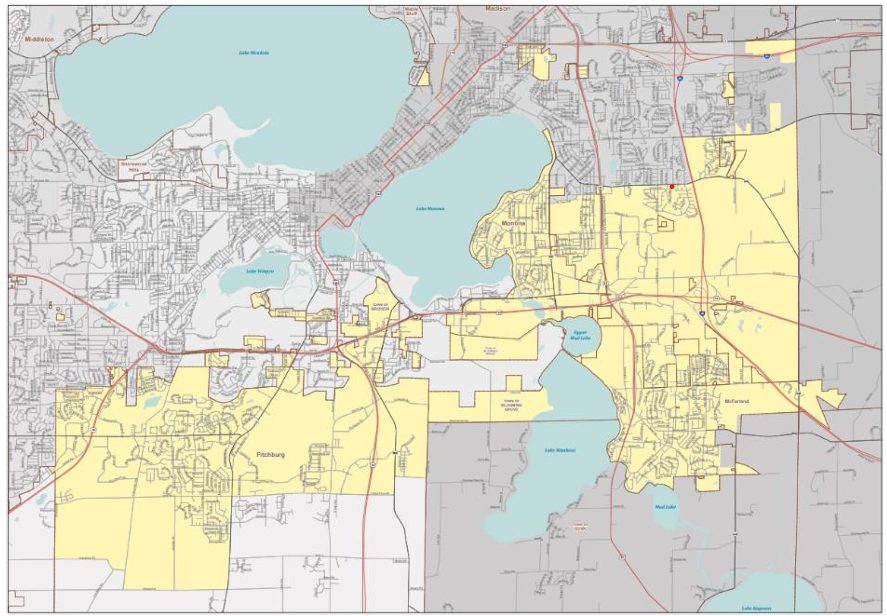

*** To be clear, this case is nothing more than a now time-barred motion to reconsider Johnson. An honest look at the plain law would require that this petition be dismissed. Instead, the creative legal machinations engaged in by the masters of this lawsuit, emboldened and encouraged by the new court of four, requires mind-boggling contortion of the law to achieve a particular political outcome. Sadly, judicial activism is once again alive and well in Wisconsin, creating great instability. *** (R)ejecting the Johnson I dissent's assertion that the task of adopting remedial maps required this court to rule as a partisan actor, we adopted "[a] least-change approach[, which] is the most consistent, neutral, and appropriate use of our limited judicial power to remedy the constitutional violations in this case." Least change, as a framework this court put forward throughout the Johnson litigation, properly reflects the limited role the judicial branch plays in redistricting, as it is the legislature, not the judiciary, which is granted constitutional authority to redistrict. Least change remains the law. Until today. Now, the majority, citing to nothing, declares instead that the standard this court implemented barely two years ago "is unworkable in practice," simply so that they can overrule it, and move this institution down the darkened path of outcome-based judicial activism. *** Ziegler then discusses at length the issues of stare decisis (adherence to precedents), standing (ability to sue), judicial estoppel (a party asserting inconsistent positions during litigation), issue preclusion (barring an argument that was previously decided, claim preclusion (barring an argument that could have been previously decided), laches (sitting on one’s rights), and due process. *** In the issue preclusion discussion: As a side note, the parties attempted to backdoor considerations of "partisan fairness" or "partisan gerrymandering" back into the court's analysis by way of at least initially confining it to the remedy phase. The majority continues that ill-fated venture of taking up an issue that both this court and the United States Supreme Court have determined is non-justiciable,67 by attempting to wrap it up in the perhaps more pleasant euphemism of "partisan impact," which the majority "will consider. . . . when evaluating remedial maps." Never mind figuring out how exactly the majority plans to go about evaluating "partisan impact" or determining how much "partisan impact" is permissible and how much is too much. They provide no measurable standard for calculating it. Apparently then, it is for them to know, and for us to find out! "The fact that the majority imposes its own unique and undefined standard further demonstrates that it exercises its will rather than its judgment." *** This court must not allow a non-justiciable, political question like partisan fairness to be camouflaged into the majority's decision. The majority declines to put forward a measurable standard by which this court is supposed to define or determine "partisan impact," demonstrating that they "exercise[]. . . . [their] will rather than [their] judgment." Their standard-deficient approach evokes recollections of the "eyeballing" tests from bygone legal eras encapsulated in "we'll know it when we see it" terminology. This court has already addressed the issues of partisan gerrymandering and political fairness, as well as contiguity. Issue preclusion bars us now from allowing these relevant parties to relitigate what has already been litigated. *** In the laches discussion: This court had a different composition two years ago, but that fact alone cannot be why these parties chose not to actively participate in that litigation at that time. To the dispassionate observer, such contortions of the law appear questionable and should come with consequences. Surprisingly, the parties are forthright enough to tell us themselves that this is in fact their reason for bringing this claim now—after waiting two years in alleged ongoing state of harm—to ensure that this case coincided with the changed composition of the court. It defies reason for parties to sit out litigation, obtain the benefit of seeing how arguments are presented, and then with that benefit of hindsight, bring their now modified claims over the same issues, with the same legal representation, at their leisure, years later. It further defies reason that given those same facts, and the fact that the respondents would not have had knowledge of the parties bringing new claims over the same maps a year later, that the parties can now demand that this court provide them an extraordinary remedy (overturning decades of precedent and the votes of millions of Wisconsinites), and do so in a constrained timeframe of mere months before another round of elections gets underway. Such unnecessary fast tracking due to the parties' own inexplicable delay may rightfully raise questions of intrusion on the opposing party's rights to fully litigate the claims presented. *** In the due process discussion: The parties interested in Justice Protasiewicz's election are intricately involved with, and beneficiaries of, the case they filed directly before her in this original action right after she was sworn in. Their timing of selecting her as their judge and then bringing this petition is irrefutable. Now, the four members of the court have fast-tracked this litigation, bypassing and rushing the traditional court steps, processes, and the law. *** In conclusion: This original action should never have been accepted. It is nothing more than a motion for reconsideration, which is time-barred; ignores stare decisis, standing, judicial estoppel, issue preclusion, claim preclusion, and laches. Not only is this a fundamentally legally flawed proceeding for these preceding listed reasons, but it also raises serious question regarding . . . whether this proceeding is a violation of litigants’ due process rights. What’s next? Pre-selected “consultants” who will decide the fate of Wisconsin voters even though the Wisconsin Supreme Court already decided these issues conclusively in the Johnson litigation? Will these “consultants” be endowed with the authority to reach all factual and legal conclusions necessary to draw the maps, while evading review and the constitutional protections due the parties? The four rogue members of the court have upended judicial practices, procedures, and norms, as well as legal practices, procedures, and precedent, yielding only to sheer will to create a particularized outcome which will please a particular constituency. At a minimum, this is harmful to the judicial branch and the institution as a whole. I dissent. Note: We are crunching Supreme Court of Wisconsin decisions down to size. The general rule for WJI's "SCOW docket" posts is that no justice gets more than 10 paragraphs as written in the actual decision, and all parts of the decision (majority, concurrences, dissents) are contained in one post. . This one is a little different, though. This time, with this case, we are doing it in three parts: first the majority decision, then the longest dissent, then the remaining two dissents. Why? Because this package of writings is extremely important: redistricting of the Legislature. In addition, the opinions are extremely long – 229 pages in all. Due to the size of the opinions, we are giving the majority opinion writer 18 paragraphs and each other opinion writer 15. Other than that, the rules remain the same. The "upshot" and "background" sections do not count as part of the paragraph restrictions because of their summary and very necessary nature. We've removed citations from the opinion for ease of reading (except, in this particular case, regarding some dictionary definitions), but may link to important cases cited or information about them. Italics indicate WJI insertions except for case names and emphasis added by the opinion writer, all of which also are italicized. The case: Rebecca Clarke v. Wisconsin Elections Commission Majority: Justice Jill J. Karofsky (51 pages), joined by Justices Ann Walsh Bradley, Rebecca Dallet, and Janet Protasiewicz Dissents: Chief Justice Annette Kingsland Ziegler (89 pages), Justice Rebecca Grassl Bradley (56 pages plus an appendix of 11 pages), and Justice Brian Hagedorn (22 pages)  Karofsky Karofsky The upshot We hold that the contiguity requirements in Article IV, Sections 4 and 5 mean what they say: Wisconsin's state legislative districts must be composed of physically adjoining territory. The constitutional text and our precedent support this common-sense interpretation of contiguity. Because the current state legislative districts contain separate, detached territory and therefore violate the constitution's contiguity requirements, we enjoin the Wisconsin Elections Commission from using the current legislative maps in future elections. We also reject each of Respondents' defenses. We decline, however, to (invalidate) the results of the 2022 state senate elections. Because we enjoin the current state legislative district maps from future use, remedial maps must be drawn prior to the 2024 elections. The legislature has the primary authority and responsibility to draw new legislative maps. Accordingly, we urge the legislature to pass legislation creating new maps that satisfy all requirements of state and federal law. We are mindful, however, that the legislature may decline to pass legislation creating new maps, or that the governor may exercise his veto power. Consequently, to ensure maps are adopted in time for the 2024 election, we will proceed toward adopting remedial maps unless and until new maps are enacted through the legislative process. At the conclusion of this opinion, we set forth the process and relevant considerations that will guide the court in adopting new state legislative districts—and safeguard the constitutional rights of all Wisconsin voters. Background Following the 2020 census, the legislature passed legislation creating new state legislative district maps, the governor vetoed the legislation, and the legislature did not attempt to override his veto. Because the legislature and the governor reached an impasse, the 2011 maps remained in effect, even though they no longer complied with the Wisconsin or United States Constitutions due to population shifts. Billie Johnson and other Wisconsin voters asked this court to redraw the unconstitutional 2011 maps. In that case, we first confirmed that the 2011 maps no longer complied with the state and federal requirement that districts be equally populated (the "Johnson I" decision). Next, we identified the principles that would guide the court in adopting new maps, including the proposition that remedial maps "'should reflect the least change' necessary for the maps to comport with relevant legal requirements." We then invited the parties to submit proposed state legislative maps for our review. Of the proposed maps, we adopted the Governor's (the "Johnson II" decision). The United States Supreme Court summarily reversed that decision, holding that the Governor's proposed legislative maps violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment because they increased the number of majority-Black districts in the Milwaukee area without sufficient justification. On remand, we adopted the legislative maps proposed by the Legislature (the "Johnson III" decision). In this case, the Clarke Petitioners filed a petition for leave to commence an original action challenging the maps adopted in Johnson III, arguing that they: (1) are an extreme partisan gerrymander; (2) do not comply with the contiguity requirements contained in Article IV, Sections 4 and 5 of the Wisconsin Constitution; and (3) were created via a process that violated the separation of powers. We granted leave in part, allowing Petitioners' contiguity and separation-of-powers claims to proceed, while declining to review the issue of extreme partisan gerrymandering. We explained that although Petitioners' extreme- partisan-gerrymandering claim presented an important and unresolved legal question, we declined to address it due to the need for extensive fact-finding. The court heard oral argument on Nov. 21, 2023. The guts We start our analysis with Article IV, Section 4 of the Wisconsin Constitution, which sets the ground rules for how Wisconsin Assembly members are elected and how their districts are to be established. . . . Section 4 imposes three separate requirements for establishing assembly districts. The districts must: (1) "be bounded by county, precinct, town or ward lines;" (2) "consist of contiguous territory;" and (3) "be in as compact form as practicable." Article IV, Section 5 sets out rules for how senators are elected and how their districts are established . . . . Section 5 imposes three requirements on senate districts. The senate districts must (1) be "single districts;" (2) be "of convenient contiguous territory;" and (3) not divide any assembly districts. *** . . . . It is immediately apparent, using practically any dictionary, that contiguous means "touching" or "in actual contact." See, e.g., Contiguous, Black's Law Dictionary, (11th ed. 2019) ("Touching at a point or along a boundary."); Contiguous, Oxford English Dictionary (2d ed. 1989) ("touching, in actual contact, next in space; meeting at a common boundary, bordering, adjoining"); Contiguous, Merriam Webster Dictionary (11th ed. 2019) ("being in actual contact: touching along a boundary or at a point"). These definitions make clear that contiguous territory is territory that is touching, or in actual contact. In other words, a district must be physically intact such that a person could travel from one point in the district to any other point in the district without crossing district lines. We find additional support for this understanding of contiguity in historical definitions and early Wisconsin districting practices. In examining historical definitions of the word "contiguous," we see that the definition has not changed since the Wisconsin Constitution was adopted. See Contiguous, A Dictionary of the English Language (1756) ("meeting so as to touch; bordering upon each other; not separate"); Contiguous, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828) ("touching: meeting or joining at the surface or border"). Turning to early districting practices, the first state legislative districts, set forth in the Wisconsin Constitution, were all physically contiguous. Additionally, the constitution specified that if existing towns were split or new towns were created, the districts had to remain physically intact. In short, historical definitions and practices related to contiguity bolster our conclusion that contiguity does indeed require "touching," or "actual contact." Respondents assert that a district with separate, detached territory can still be contiguous—so long as the detached territory is a "municipal island" (meaning portions of municipal land separated from the main body of the municipality, usually created by annexation) and the main body of the municipality is located elsewhere in the district. The Legislature refers to this as "political contiguity." Adopting the concept of political contiguity would essentially require us to read an exception into the contiguity requirements—that district territory must be physically touching, except when the territory is a detached section of a municipality located in the same district. We decline to read a political contiguity exception into Article IV's contiguity requirements. The text contains no such exception. Both Section 4 and Section 5 include the discrete requirement that districts be composed of contiguous territory. There are no exceptions to contiguity in the constitution's text, either overt or fairly implied. True, assembly districts must also be "in as compact form as practicable" and "bounded by county, precinct, town or ward lines," but the existence of additional requirements does not constrain or limit the separate requirement that district territory be contiguous. The court then discussed two prior cases, from 1880 and 1892, that confirmed the court’s understanding of contiguity. *** None of the parties disputes that the current legislative maps contain districts with discrete pieces of territory that are not in actual contact with the rest of the district. We . . . look at the example of Assembly District 47 (in yellow) which plainly includes separate, detached parts: The court provided additional examples with images.

*** In total, at least 50 assembly districts and at least 20 senate districts include separate, detached parts. That is to say, a majority of the districts in both the assembly and the senate do not consist of "contiguous territory" within the meaning of Article IV, Section 4, nor are they "of convenient contiguous territory" within the meaning of Article IV, Section 5. Therefore, we hold that the non-contiguous legislative districts violate the Wisconsin Constitution. *** As we declared above, the current legislative maps contain districts that violate Article IV, Sections 4 and 5 of the Wisconsin Constitution. At least 50 of 99 assembly districts and at least 20 of 33 senate districts contain territory completely disconnected from the rest of the district. Given this pervasiveness, a remedy modifying the boundaries of the non-contiguous districts will cause a ripple effect across other areas of the state as populations are shifted throughout. Consequently, it is necessary to enjoin the use of the legislative maps as a whole, rather than only the non-contiguous districts. We therefore enjoin the Wisconsin Elections Commission from using the current legislative maps in all future elections. Accordingly, remedial legislative district maps must be adopted. We recognize that next year's legislative elections are fast-approaching, and that remedial maps must be adopted in time for the fall primary in August 2024. With that in mind, the following section first describes the role of the court in the remedial process. Second, we articulate the principles the court will follow when adopting remedial maps. . . . It is essential to emphasize that the legislature, not this court, has the primary authority and responsibility for drawing assembly and senate districts. Therefore, when an existing plan is declared unconstitutional, it is "appropriate, whenever practicable, to afford a reasonable opportunity for the legislature to meet constitutional requirements by adopting a substitute measure." There may be exceptions to this general rule, but we decline Petitioners' request to apply one here. Should the legislative process produce a map that remedies the contiguity issues discussed above, there would be no need for this court to adopt remedial maps. We remain cognizant, however, of the possibility that the legislative process may not result in remedial maps. In such an instance, it is this court's role to adopt valid remedial maps. The United States Supreme Court has specifically recognized the ability of a state judiciary to remedy unconstitutional legislative districts by crafting new remedial maps. And this court has exercised such authority in the past when faced with unconstitutional maps. If the legislative process does not result in remedial legislative maps, then it will be the job of this court to adopt remedial maps. *** The court then rejected and overruled the “least change” approach used in the Johnson cases (meaning that remedial maps should reflect the least change from the prior maps) because the court had failed to agree on what "least change" meant and the method was shown to be “unworkable in practice.” The following principles will guide our process in adopting remedial legislative maps. First, the remedial maps must comply with population equality requirements. State and federal law require a state's population to be distributed equally amongst legislative districts with only minor deviations. When it comes to population equality, courts are held to a higher standard than state legislatures as we have a "judicial duty to 'achieve the goal of population equality with little more than de minimis variation.'" Second, districts must meet the basic requirements set out in Article IV of the Wisconsin Constitution. Assembly districts must be (a) bounded by county, precinct, town or ward lines; (b) composed of contiguous territory; and (c) in as compact form as practicable. Senate districts must be composed of "convenient contiguous territory." Additionally, districts must be single-member districts that meet the numbering and nesting requirements set out in Article IV, Sections 2, 4, and 5. *** Third, remedial maps must comply with all applicable federal law. In addition to the population equality requirement discussed above, maps must comply with the Equal Protection Clause and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Fourth, the court will consider other traditional districting criteria not specifically outlined in the Wisconsin or United States Constitution, but still commonly considered by courts tasked with formulating maps. These other traditional districting criteria include reducing municipal splits and preserving communities of interest. These criteria will not supersede constitutionally mandated criteria, such as equal population requirements, but may be considered when evaluating submitted maps. Fifth, we will consider partisan impact when evaluating remedial maps. When granting the petition for original action that commenced this case, we declined to hear the issue of whether extreme partisan gerrymandering violates the Wisconsin Constitution. As such, we do not decide whether a party may challenge an enacted map on those grounds. However, that does not mean that we will ignore partisan impact in adopting remedial maps. Unlike the legislative and executive branches, which are political by nature, this court must remain politically neutral. We do not have free license to enact maps that privilege one political party over another. Our political neutrality must be maintained regardless of whether a case involves an extreme partisan gerrymandering challenge. As we have stated, "judges should not select a plan that seeks partisan advantage—that seeks to change the ground rules so that one party can do better than it would do under a plan drawn up by persons having no political agenda—even if they would not be entitled to invalidate an enacted plan that did so." Other courts have held the same. It bears repeating that courts can, and should, hold themselves to a different standard than the legislature regarding the partisanship of remedial maps. As a politically neutral and independent institution, we will take care to avoid selecting remedial maps designed to advantage one political party over another. Importantly, however, it is not possible to remain neutral and independent by failing to consider partisan impact entirely. As the Supreme Court (has) recognized . . . "this politically mindless approach may produce, whether intended or not, the most grossly gerrymandered results." As such, partisan impact will necessarily be one of many factors we will consider in adopting remedial legislative maps, and like the traditional districting criteria discussed above, consideration of partisan impact will not supersede constitutionally mandated criteria such as equal apportionment or contiguity. The Wisconsin Supreme Court just issued a decision in Clarke v. Wisconsin Elections Commission invalidating the current Assembly and Senate maps based on the petitioners' contiguity argument. The court ruled 4 to 3, with Justice Jill Karofsky writing the majority opinion. The court stated in pertinent part as follows:

¶3 We hold that the contiguity requirements in Article IV, Sections 4 and 5 mean what they say: Wisconsin's state legislative districts must be composed of physically adjoining territory. The constitutional text and our precedent support this common-sense interpretation of contiguity. Because the current state legislative districts contain separate, detached territory and therefore violate the constitution's contiguity requirements, we enjoin the Wisconsin Elections Commission from using the current legislative maps in future elections.8 We also reject each of Respondents' defenses. We decline, however, to issue a writ quo warranto invalidating the results of the 2022 state senate elections. ¶4 Because we enjoin the current state legislative district maps from future use, remedial maps must be drawn prior to the 2024 elections. The legislature has the primary authority and responsibility to draw new legislative maps. See Wis. Const. art. IV, § 3. Accordingly, we urge the legislature to pass legislation creating new maps that satisfy all requirements of state and federal law. We are mindful, however, that the legislature may decline to pass legislation creating new maps, or that the governor may exercise his veto power. Consequently, to ensure maps are adopted in time for the 2024 election, we will proceed toward adopting remedial maps unless and until new maps are enacted through the legislative process. At the conclusion of this opinion, we set forth the process and relevant considerations that will guide the court in adopting new state legislative districts——and safeguard the constitutional rights of all Wisconsin voters. WJI will report more on this decision but wanted to get this news out to you. Here's the full opinion, including the dissents (all 225 pages). By Alexandria Staubach

If the Wisconsin Supreme Court decides in the pending redistricting litigation that current Wisconsin legislative maps are unconstitutional, the decision will be based on one of two legal arguments. Last week, WJI unpacked one, the contiguity argument. We now turn to the second argument: separation of powers. The court heard oral arguments in late November. At that hearing, the conservative minority of the court raised the concern that all issues currently before the court were or should have been decided in a series of cases (Johnson I, Johnson II, and Johnson III) before the court in 2021 and 2022. Redistricting in Wisconsin takes place every 10 years following the federal census; the most recent census year was 2020. In November 2021, the Republican-led Legislature passed new maps based on the 2020 census data. Gov. Evers vetoed those maps shortly afterward, and his veto was never overridden by the Legislature. Thus, those maps are said to have “failed the political process.” The adoption of new maps then fell to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, which in Johnson I said it would apply a “least change” approach, meaning the court would adopt the proposed maps that made the fewest changes to those adopted following the 2010 census. In Johnson II, the court adopted maps proposed by Gov. Evers because the administration’s maps moved the smallest number of Wisconsinites to new districts under a theory called “core retention.” Evers’ maps also created a new majority Black district in Milwaukee. In opposition to the majority’s decision, Justice Rebecca Grassl Bradley said “core retention—exists nowhere in the … Wisconsin Constitution or any statutory law” and that it was a “dangerous doctrine.” The court’s decision was challenged and reversed in the U.S. Supreme Court on the basis that the Wisconsin Supreme Court provided insufficient analysis of whether an additional Black majority district in Evers’ map was supported and permitted by the Voting Rights Act. On remand from the U.S. Supreme Court, in Johnson III, the Wisconsin Supreme Court adopted the maps submitted to the court by the Republican-led Legislature, which were the same maps vetoed by Evers. The Clarke petitioners argue that the court’s adoption in Johnson III of the same maps vetoed by the governor violated the Wisconsin Constitution’s separation of powers, disrupting the distribution of power between co-equal branches of government. In her dissent to the court’s order taking jurisdiction of the Clarke case, Chief Justice Annette Kingsland Zeigler said the argument “does not seem to warrant serious review,” and the court was “forced” to “select constitutionally compliant maps as a remedy for the [then] ongoing constitutional violation.” In this, Zeigler failed to acknowledge that the court was not bound to simply choose the maps promulgated by the Legislature. As Justice Jill J. Karofsky pointed out in her dissent in Johnson III, the court could have invited more briefing to ascertain whether the governor’s maps comported with the Voting Rights Act or asked the parties or a neutral map drawer to submit redrawn race-neutral maps. Instead, Karofsky said, the court overrode the governor’s veto, “nullifying the will of the Wisconsin voters who elected that governor into office.” While the current majority of the court did not seem overly interested in the separation of powers argument at hearing, the issue may play some role moving forward. Attorney Anthony Russomanno, representing the governor at oral argument in Clarke, principally addressed the separation-of-powers argument. The three conservative justices immediately pressed Russomano on why the issue was not raised during the Johnson litigation. Russomano argued that the separation-of-powers argument did not arise until the court adopted the Legislature’s maps at the end of the Johnson litigation. Justice Brian Hagedorn noted that the Legislature’s role is to pass law and the court passed no laws, so therefore he could not see how the court in imposing a judicial remedy could have violated separation of powers requirements. Russomano was not afforded the opportunity to respond before being redirected to discuss whether and how to address partisanship in maps. Wisconsin Justice Initiative (WJI) and the Wisconsin Fair Maps Coalition (FMC) together filed a friend-of-the-court (amici) brief in Clarke. WJI and FMC argued that Wisconsinites have no direct means to enact law and their voice rests in the governor. The imbalance of power resulting from the current legislative maps frequently permits a minority view to predominate the majority’s view, and the governor’s role is to counter act that imbalance. WJI and FMC argued that because the maps submitted by the Legislature were vetoed by the governor they “should have been ineligible for consideration” by the Johnson III court under separation-of-powers principles and the Wisconsin Constitution. By Alexandria Staubach

Arguments at last week’s Wisconsin Supreme Court hearing in Clarke v. Wisconsin Elections Commission, the most recent case to challenge gerrymandered districts across Wisconsin, beg the question, have we been here before? In Clarke, the court agreed to hear two of five issues raised by the petitioners:

If you read or heard anything about the court’s Nov. 21 hearing, the report likely included some reference to Justice Rebecca Grassl Bradley’s position that 1) the contiguity argument presented in Clarke was already decided by the 2021-2022 Johnson cases (the last legal go-round about the current maps, which resulted in three separate opinions by the Wisconsin Supreme Court), and 2) this case wouldn’t be before the court but for its new majority. Grassl Bradley interjected at seemingly every feasible opportunity to assert that this case would not be before the court absent the election of Justice Janet Protasiewicz and threw in mention of Protasiewicz’s campaign comments that the maps are rigged. Another justice asked if Grassl Bradley was in fact arguing the case. Article IV, section 4 of the Wisconsin Constitution requires that Assembly districts “consist of contiguous territory and be in as compact form as practicable.” Numerous Assembly districts include “islands” or detached pieces that are located completely within other districts, with no physical connection. However, the detached pieces are generally annexed to a municipality that has a physical connection to other parts of the district. The question in Clarke is whether these detached pieces are considered contiguous and satisfy the Constitution's requirements. Grassl Bradley referenced, and Taylor Meehan, counsel for the Republican Legislature, cited by paragraph where and when, the contiguity argument in Clarke was disposed of in the 2022 Johnson III decision (the final Johnson opinion, in which the current maps were adopted by the court). So let’s examine Grassl Bradley’s claim that the court already decided the issue of contiguity. The word “contiguous” appears five times in the 23-page Johnson III opinion. Nearly every mention is a recitation of the requirements of the Wisconsin Constitution regarding legislative districting. According to Meehan and accepted by Grassl Bradley at argument, the Johnson III paragraph that purportedly decided the contiguity argument reads as follows: ¶70 The Legislature has satisfied the remainder of Wisconsin’s constitutional requirements. The assembly districts are contiguous and sufficiently compact. Wis. Const. art. VI, sec. 4. Both senate and assembly maps include single member districts, and assembly districts are not divided in the formation of senate districts. Wis. Const. art. IV, secs. 4, 5. In all, the Legislature’s senate and assembly maps comply with the Wisconsin Constitution. This paragraph comes at the end of the opinion but is not part of the court’s conclusion. Johnson III’s conclusion was that insufficient evidence was presented “to justify drawing state legislative districts on the basis of race,” and that the maps proposed by Gov. Tony Evers and parties other than the Legislature were racially motivated. Paragraph 70, as relied on by Meehan in arguing against the Clarke petitioners, supposedly disposes of unargued requirements of the Wisconsin Constitution simply by saying that in the court’s view, the maps at issue in Johnson III are constitutional. Is this passing reference sufficient to resolve the contiguity issue? Have we been here before? Grassl Bradley and other conservative justices are using the principle of issue preclusion to say, “yes,” contiguity has been resolved and is now barred in the new case. For issue preclusion to apply, Wisconsin law requires identity between parties in the previous case and the current case and that the issue or fact be actually litigated and determined in the previous case. In this context, identity between parties would require that the same parties or interests who initiated the Johnson case match those in the Clarke case. In Clarke, the petitioners are 19 Wisconsin voters, none of whom was a party in the Johnson case. Some of the Clarke petitioners share counsel with those in the Johnson case, but counsel are not parties. Additionally, some of the respondents, such as the Wisconsin Election Commission, are shared between the two cases, but this should not be sufficient to create “identity” of parties under Wisconsin law. Further, while maps at issue in Clarke are the same maps adopted in Johnson III, contiguity was not the issue litigated in the Johnson case. At issue in Johnson was how maps should be drawn when the legislative process failed and to what extent legislative districts could be drawn giving attention to race. Passing mention of contiguity, according to the Clarke petitioners’ brief, is not sufficient for finding that the issue was litigated under Wisconsin law, and the petitioners contend that “no party in Johnson claimed that any existing or proposed remedial districts were noncontiguous” and that “in their voluminous briefing in Johnson, the parties hardly mentioned contiguity.” The Wisconsin Supreme Court took jurisdiction of the Clarke case on Oct. 6 without mentioning issue preclusion. However, a dissent written by Chief Justice Annette Ziegler, joined by Grassl Bradley and Justice Brain Hagedorn, did. Ziegler wrote that Wisconsin law requires the petitioners in this case to “live with” the Johnson decision and that litigation involving the same maps “should not be allowed to prevail.” In a separate dissent, written with reference to Alice in Wonderland as an underlying theme, Grassl Bradley, joined by Ziegler, wrote that “(r)edistricting litigation concluded — or at least it should have — in April 2022, with this court’s selection of new maps as a remedy for malapportionment.” Whether and to what extent the now-minority conservative justices will rely on issue preclusion in any decision in the case remains to be seen, but at least in the eyes of the petitioners and the court’s current majority, we have not been here before. By Margo Kirchner

Wisconsin Justice Initiative and the Wisconsin Fair Maps Coalition (FMC) on Wednesday jointly filed a motion seeking leave to submit an amicus curiae (friend of the court) brief in the redistricting case before the Wisconsin Supreme Court. The case concerns whether the present voting-district maps for the Wisconsin Legislature violate the Wisconsin Constitution’s requirements regarding contiguous districts and separation of powers between the three government branches. Districting maps are to be adjusted every 10 years after census results are published. The present districting maps were adopted by the Supreme Court in spring 2022 after the legislative process failed. Gov. Tony Evers vetoed redistricting maps passed by the Legislature, and the Legislature failed to override the veto. The Wisconsin Supreme Court first adopted a set of maps that were invalidated by the U.S. Supreme Court. The Wisconsin Supreme Court then adopted the same maps from the Legislature that Evers had vetoed. When vetoing those maps, Evers referenced how highly partisan they were. He said he’d promised he would never sign gerrymandered maps and his veto delivered on that promise. In their proposed brief, WJI and FMC argue from the viewpoint of the overwhelming number of Wisconsin citizens who demand nonpartisan district maps and whose voices are not being acknowledged by the Legislature. FMC is an umbrella organization of numerous local and regional fair-maps activist groups. WJI and FMC contend that the court’s adoption of the current maps constituted an impermissible judicial override of Evers’ veto, in violation of separation-of-powers requirements in the state constitution. WJI and FMC further argue that in crafting any new set of maps as a remedy, the court must take into account the partisan effects of those maps and the people’s demand for nonpartisan maps. WJI and FMC argue in their brief that by failing to consider the partisan effects of the maps it chooses, as the court did in 2022, the court actually acts in a partisan manner. Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce also seeks leave to file an amicus brief. Notably, WMC states in its motion that it has a “strong interest” in the case because “WMC and its members have forged relationships with the representatives elected pursuant to the current maps” and “(m)embers of WMC have relied on political vows made by those same representatives.” Other individuals and organizations seeking leave to file amicus briefs: