By Margo Kirchner A federal judge’s refusal to delay trial for two years so that “Coupon King” Thomas (Chris) Balsiger could be represented by a particular lawyer did not violate Balsiger’s right to counsel, a federal appeals court ruled last week. The ruling means that the 10-year federal criminal case against Balsiger will not be retried. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit affirmed the bulk of Balsiger’s conviction and sentence with the exception of a recalculated forfeiture amount. Balsiger ran International Outsourcing Services, one of the nation’s largest product-coupon processors, in El Paso, Texas, and Bloomington, Indiana. He and 10 others were indicted in 2007 on 25 counts of wire fraud, conspiracy to commit wire fraud, and conspiracy to obstruct justice. The fraud allegations involved coupon payments made by Wisconsin manufacturers Sargento Foods, Good Humor/Breyers Ice Cream, Kimberly-Clark, LeSaffre Yeast, and S.C. Johnson & Sons. The indictment alleged that the wire-fraud scheme caused $250 million in losses to manufacturers. Pretrial proceedings dragged on for years. During that time, in July 2014, Balsiger’s lawyer, Joseph Sib Abraham, passed away. U.S. District Judge Charles N. Clevert, Jr. was notified in August 2014, and a lawyer who worked with Abraham said Balsiger expected to hire new counsel within 30 days. Yet by early December 2014 no new attorney had appeared in the case and Balsiger claimed he could not then hire a new attorney due to financial difficulties. Clevert set trial for October 2015. At a status conference in early January 2015 Balsiger told Clevert he planned to hire El Paso attorney Richard Esper, and asked for a deadline of April 1, 2015, to hire Esper. Balsiger said he did not have sufficient funds and could not sell his home because of a filing the government made against the property. Clevert soon learned that Esper could not be ready for trial until 2017 at the earliest. The judge also found that Balsiger could afford to hire a lawyer and ordered him to hire someone by Feb. 17, 2015. The court found that Balsiger was not working diligently to hire counsel and warned that failure to hire an attorney would be considered a waiver of the right to counsel.

0 Comments

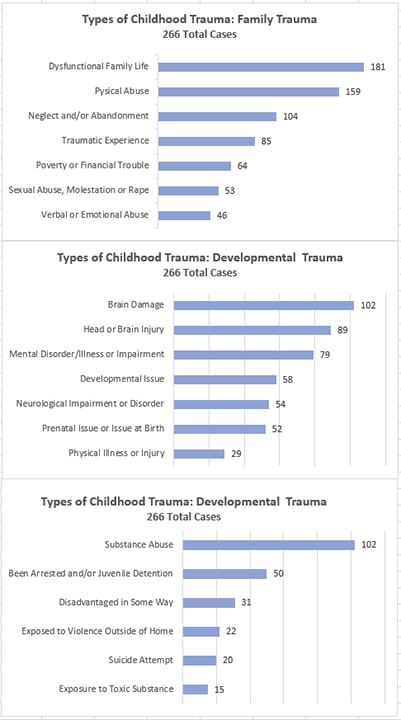

Wood Wood By Margo Kirchner Robert W. Huber Jr. spent 18 years too many in prison or on probation because of bureaucratic blunders and refusal to listen to his protests. Now a federal appeals court has cleared the way for his civil rights lawsuit to proceed. Huber is seeking damages for violations of his constitutional rights. U.S. District Judge J.P. Stadtmueller granted summary judgment to the defendants, holding that Wisconsin’s six-year statute of limitations barred most of Huber’s claims and that no reasonable jury could find in Huber’s favor on any remaining ones. Huber appealed. On Monday, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals reversed, reinstated Huber’s claims, and remanded the case for further proceedings. The appellate court denied Huber’s request to reassign the case to a different district judge, however. Huber pleaded guilty in 1988 in Milwaukee County Circuit Court to fraudulently using another man’s credit card for charges totaling $800. His sentence, originally a four-year probation term, turned into a 25-year odyssey of probation and prison. First, an additional three years of probation were tacked on because Huber failed to pay restitution. “With that extension, his sentence should have ended on November 3, 1995,” U.S. Circuit Judge Diane P. Wood wrote for the three-judge panel of the Seventh District Court of Appeals. “But it did not.” Wood was joined in her opinion by U.S. Circuit Judges Joel M. Flaum and Frank H. Easterbrook. First, in May 1993 and while still on paper, Huber stopped showing up for appointments with his probation agent. He was arrested in November 1994, but the state did not move to revoke his probation or to extend it. His agent even wrote that his discharge date was “11-3-95.” Later, in her last entry before Huber’s discharge date, the agent wrote, “no changes – all ok.” “November 3 came and went without any action; no release, no modification of Huber’s probation, no formal extension,” Wood wrote. “Two weeks later, without any reference to her repeated notes acknowledging the November 3, 1995 release date, (Probation Agent Gloria) Anderson issued an apprehension request for Huber.” Huber argued for years that his probation term expired on the November 3, 1995 date. But, he alleges, various probation officers and Wisconsin Department of Corrections (DOC) officials did little or nothing to investigate whether his probation was illegally extended. Not until October 2013 did officials determine that Huber was right. Huber was arrested in January 1996, not terribly long after Anderson issued her apprehension request. Anderson and her supervisor, Elizabeth Hartman, then told him that his probation had been suspended from May 1993 to November 1994 and he still had time to serve. They had him sign a form requesting reinstatement of his probation. Huber alleges that the form was blank at the time and changed later to make it appear that he admitted to absconding from probation. Huber’s probation was extended to July 1998. Another absconding led to more extensions, until in October 2000 Huber’s probation was revoked, resulting in a 10-year prison sentence for an $800 credit card fraud conviction that originally netted him four years of probation.  Denno Denno By Margo Kirchner Defense attorneys are failing their clients if they neglect to understand, investigate, and present evidence of childhood trauma in criminal cases, says a legal and neuroscience expert. Deborah W. Denno, a professor and founding director of the Neuroscience and Law Center at Fordham University School of Law, spoke last week at Marquette University Law School. Denno obtained her law degree and a Ph.D. in sociology from the University of Pennsylvania and has taught at Fordham Law, the London School of Economics, Columbia Law School, and Princeton University. She visited Marquette Law to give the annual Barrock Lecture on Criminal Law, presenting her research and conclusions about the use of childhood-trauma evidence in adult criminal cases. Denno studied criminal cases reported nationwide, investigating how defense attorneys introduced and how courts assessed the mitigating and aggravating impacts of neuroscience evidence. Neuroscience is the branch of life science focusing on the brain and nervous system. Denno researched written court decisions reported in the online legal databases Westlaw and Lexis from 1992 to 2012. She found 800 criminal cases involving neuroscience evidence. She reviewed those and then narrowed her focus to the 266 cases involving childhood trauma. Denno acknowledged that written opinions reported in Westlaw and Lexis are predominantly from appellate courts, so her research similarly involved mostly appellate court decisions. Further, almost all of the 266 cases she reviewed in depth were homicide cases, and most involved the death penalty. She looked particularly at the types of childhood trauma defendants had suffered, conditions caused by or related to the trauma, how evidence of the trauma or conditions was presented to courts, and the courts’ responses. From the 266 cases she identified 20 types of trauma, which she grouped as either family, developmental, or external trauma. On average, each defendant in the 266 cases had suffered five different types.  Barrett Barrett By Margo Kirchner A federal appeals court last week vacated a $10 million award to employees of Pewaukee’s Waterstone Mortgage Corporation for wage and hour violations because the claimants arbitrated as a group. The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, citing the U.S. Supreme Court decision in another Wisconsin-based case involving Epic Systems, of Verona, held that a Waterstone employee’s employment agreement limiting arbitration to a single claimant does not violate the National Labor Relations Act’s protections. Pamela Herrington sued Waterstone in U.S. District Court in Madison, asserting that the company failed to pay her minimum wages and overtime as required by the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). Under FLSA, claims may be brought as collective actions, meaning that other employees may opt in to the lawsuit. Herrington filed her case as a collective action and 174 other Waterstone employees eventually joined her case. Herrington’s employment agreement, however, contained an arbitration clause covering employment disputes. The clause said Herrington’s arbitration could not be joined with or include any claims by others against Waterstone. U.S. District Judge Barbara B. Crabb agreed with Herrington’s argument that any waiver of the right to join the claims of others was invalid under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), which protects the right to engage in “concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection.” Crabb’s decision aligned with applicable law at the time. The National Labor Relations Board had determined that the right to engage in concerted activities for mutual aid or protection included the right to pursue collective or class claims. The Seventh Circuit later reached the same conclusion in a case involving Epic Systems. As a result, Crabb struck the portion of the arbitration clause that waived collective or class action. She then sent the case to arbitration with instructions that Herrington be allowed to join other employees in her arbitration proceedings. The arbitrator allowed other employees to opt in and, after further proceedings, awarded the claimants over $10 million in damages and fees. Crabb then enforced the award through a court judgment, and Waterstone appealed to the Seventh Circuit. While Waterstone’s appeal was pending, the U.S. Supreme Court overruled the Seventh Circuit’s decision in the Epic Systems case and held that an arbitration clause limiting arbitration to a single claimant does not violate the NLRA’s protection of concerted activities. The Supreme Court’s decision meant the waiver in Herrington’s employment agreement was lawful and Crabb was wrong to strike it, the Seventh Circuit said in the Herrington case. Herrington also argued the arbitration clause still allows for collective or class arbitration despite the waiver. U.S. Circuit Judge Amy Coney Barrett, in the decision, called the argument “weak” and suggested it was “implausible,” but remanded the case to Crabb for a determination. Barrett was joined in her decision by U.S. Circuit Judges Amy J. St. Eve and William J. Bauer. If Crabb agrees with Herrington, Crabb could confirm the $10 million award. If Crabb finds that Herrington’s arbitration is limited to her claims alone, the case could be sent back to arbitration for new proceedings. Seventh Circuit revives lawsuit alleging lengthy isolation stays at Copper Lake prison for girls10/10/2018  By Margo Kirchner The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit this week reinstated claims brought by two Iowa teens who alleged they were subject to excessive isolation and force when they were housed in Wisconsin’s Copper Lake youth prison for girls. The suit named as a defendant the Iowa official who oversaw placement of Iowa youth in the Wisconsin facility. The opinion was written by U.S. Circuit Judge Joel M. Flaum, who was joined by U.S. Circuit Judges Daniel A. Manion and Ilana Diamond Rovner. Iowa closed its female youth facility in 2014 and contracted with Wisconsin to house at Copper Lake girls found delinquent in Iowa courts. Iowa paid Wisconsin $301 per day per child. Iowa declared Laera Reed and Paige Ray-Cluney delinquent and sent them to Copper Lake in 2015. The girls were 16 at the time. Ray-Cluney says she spent five months in isolation from the end of June until December 15, 2015. Reed says that between August 2015 and February 2016 she spent between 64 and 74 days in isolation. According to Reed and Ray-Cluney, isolation meant spending 22 hours per day in a seven- by ten-foot concrete cell. The cells were stained with urine and contained only a metal cot and thin mattress. A thick cage covered the one window, reducing the light passing through. During their limited daily release from the cells, the girls were allowed only to shower, use the restroom, exercise for 15 minutes, clean their rooms, use 15 minutes to write a letter, or sit in chairs by themselves without speaking. They received little or no educational instruction. Both girls attempted suicide. In August 2017 Reed and Ray-Cluney sued Wisconsin’s Administrator of Juvenile Corrections and several Wisconsin officials associated with Copper Lake. In addition, Reed and Ray-Cluney sued Charles Palmer, director of the Iowa Department of Human Services.

Reed and Ray-Cluney filed their separate lawsuits in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin, alleging constitutional violations arising from excessive use of isolation cells and excessive force. They also alleged intentional infliction of emotional distress and negligence. Reed added violations of the Iowa constitution. The Seventh Circuit appeal involved only the claims against Palmer relating to Copper Lake’s isolation cells. The plaintiffs did not allege that Palmer knew about any use of excessive force. According to the complaints, Palmer contracted with Wisconsin to use the Copper Lake facility, retained legal custody of both plaintiffs, monitored and received reports about plaintiffs’ confinement at Copper Lake, and knew or should have known about Copper Lake’s use of isolation cells. Nevertheless, say the plaintiffs, Palmer failed to remove them from Copper Lake or ensure that Copper Lake properly trained and supervised its staff. In district court, Palmer moved to dismiss based on qualified immunity. U.S. District Judge Barbara B. Crabb agreed with Palmer and dismissed all claims against him. Reed and Ray-Cluney appealed. The plaintiffs’ claims against the Wisconsin defendants were not affected by Palmer’s dismissal. Qualified immunity protects public officials from civil liability unless their conduct violated a clearly established constitutional right that a reasonable person would have known about, the Seventh Circuit said in its opinion. The doctrine balances the need to hold public officials accountable for their irresponsible conduct and the need to protect them from liability when they perform duties reasonably. Qualified immunity does not protect a public official from suit if a plaintiff shows that the official violated a constitutional right and that right was clearly established at the time of the challenged conduct. To be clearly established, the law must “be sufficiently clear that every reasonable official would have understood that what he is doing violates that right,” said the Seventh Circuit. Judge Crabb believed that even taking the facts alleged in the complaints as true, no law clearly established what action was required of someone in Palmer’s position. The Seventh Circuit held that dismissal was premature. It noted that because the qualified immunity defense depends on the facts of each case, dismissal at an early stage (before discovery) is unusual. Plaintiffs are not required to allege in their complaints detailed facts that anticipate or defeat a qualified immunity defense. Instead, said the court, the plaintiffs need to allege only enough facts to “present a story that holds together.” The Seventh Circuit recognized that under an Eighth Amendment cruel-and-unusual-punishment test based on culpable and serious denial of life’s necessities, the plaintiffs’ allegations held up. The court pointed to a 1974 case involving use of corporal punishment and tranquilizing drugs at a juvenile institution and noted a recent case out of New York holding that juvenile isolation is likely unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment. Likewise, the Seventh Circuit found that plaintiffs’ allegations met the requirements of a more lenient Fourteenth Amendment due-process test for pretrial detainees. Under Supreme Court caselaw from the early 1980s, restrictions on liberty are permitted only if reasonably related to legitimate government objectives and not for punishment. Thus, said the court, under either test case law clearly established that Palmer’s alleged conduct could violation the Constitution. Crabb had found that unlike the officials in prior cases, Palmer did not himself oversee use of the isolation cells or operate the institution in which alleged abuse occurred. But the Seventh Circuit found that Palmer’s separation from the institution at issue and his lack of personal involvement in placing the girls in isolation did not alter the need for remand. The Seventh Circuit pointed to the special relationship created when a state removes a child from parental custody and to prior case law defining the right of a child in state custody not to be handed over to a custodian that the state knows is a child abuser. On remand, Palmer may reassert other defenses to the case, including his argument that the Wisconsin federal court lacks personal jurisdiction over him. Further, Palmer may obtain qualified immunity on summary judgment if the facts fail to support the plaintiffs’ allegations regarding the extent of their isolation or Palmer’s level of involvement and knowledge. “In the meantime, however,” said the Seventh Circuit, “this case is one that would greatly benefit from a more robust record.”  By Margo Kirchner Negligent – even reckless – horseback-riding facilities in Wisconsin are immune from liability for harm they cause customers, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit confirmed last week. The decision addressed two cases. In the first case, Holiday Stables employees sent Judy Dilley out on a horse without instructions or a helmet, even though Dilley had told a staffer she lacked prior horseback-riding experience. The employees also failed to adjust her stirrups. On the trail, Dilley told the guide riding in front of her that she did not have hold of the reins of her horse, Blue. The guide told her not to worry because Blue, who often carried small children, knew where to go. After about 20 minutes, Blue attempted to pass the guide’s horse, which kicked at Blue. Blue reared, throwing Dilley to the ground. Dilley suffered a head injury, fractured ribs and vertebra, and punctured lung. In the second case, Abigail Brown sued over multiple leg fractures sustained during a riding lesson. Brown took her own horse, Golden Gift, to Country View Equestrian Center in Monroe for the lesson. During the lesson Country View’s instructor allowed a second rider and horse to enter the arena, knowing that the second horse was high spirited. The second horse sped off, bucking and colliding with Golden Gift, tossing Brown from her horse. Both women were from out of state and so sued in federal court. They lost there and appealed. The court interpreted the state’s equine-immunity law that, with some exceptions, protects trail operators and riding instructors from paying a rider for injuries. U.S. Circuit Judge Diane Sykes wrote for the Seventh Circuit panel, joined by Circuit Judges Joel Flaum and David Hamilton. Under the statute, a person or facility renting out horses or receiving pay for riding lessons is generally immune from civil liability if a participant is injured due to “an inherent risk” of the equine activity. Holiday Stables employees sent Judy Dilley out on a horse without instructions or a helmet, even though Dilley had told a staffer she lacked prior horseback-riding experience. "Inherent risk" means “a danger or condition that is an integral part of equine activities” and includes collisions between animals, the unpredictability of a horse’s behavior or reactions to its surroundings, and the potential of a person participating in the activity to act negligently. Dilley argued that because negligence of a trail operator is avoidable, it is not an “integral part” of horseback riding and thus immunity does not arise. The Seventh Circuit rejected her argument based on the statute’s text. The court also rejected Dilley’s alternative argument that her case fit a couple exceptions to immunity. One exception permits recovery of damages when a trail operator provides a horse “and fails to make a reasonable effort to determine the ability of the person to engage safely in an equine activity or to safely manage the particular equine provided.” Dilley argued that the exception applies when the operator “fails to . . . safely manage” a horse, while Holiday argued that the exception applies only when an operator fails to assess “the ability of the person . . . to safely manage” the horse. With no Wisconsin Supreme Court interpretation of the language on the books, the Seventh Circuit predicted how the state’s high court would rule. Declaring the task “not difficult,” the Seventh Circuit agreed with Holiday’s interpretation. The exception does not affect immunity for the trail operator’s negligent management of a horse, said the court. During the lesson Country View’s instructor allowed a second rider and horse to enter the arena, knowing that the second horse was high spirited. Further, the court added, nothing in the statute suggests that immunity is lost when an operator fails to periodically review how a rider is doing; the exception concerns only the time when the rider is matched with the horse.

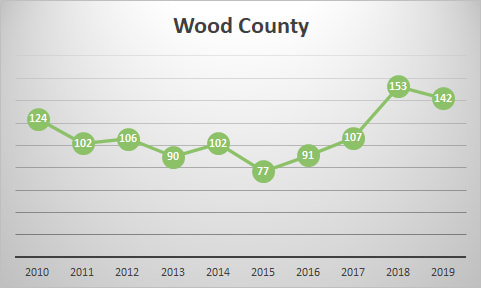

Brown argued the same exception, but lost because she rode her own horse. The exception applies only when an operator or instructor provides the horse. “[I]t strikes us as entirely reasonable that a rider who owns his own horse should bear the risk of a mismatch between his riding ability and his horse’s temperament,” Sykes wrote. Dilley also argued unsuccessfully that Holiday’s conduct was reckless, satisfying an exception for “willful or wanton disregard for the safety of the person.” The court, though, said the word “reckless” was not in the statute, as it was in other state laws. Even when an operator should be aware of a strong probability of harm and acts anyway, immunity applies, Sykes said. The court offered no sympathy for the unsuccessful plaintiffs, as courts sometimes do when ruling against them. Instead, the panel wrote a few parting words about the roles of court and legislature. Said the court: “The immunity statute and its exceptions necessarily entail policy judgments about how much exposure to liability is too much in this sphere of recreational activity. Unless the statute admits of no rational justification, it’s not our job to second-guess how Wisconsin’s legislature has drawn these lines.”  Vann-Marcouex Vann-Marcouex Updated Sept. 12, 2018 to include responses from the State Public Defender's Office and Wood County Circuit Judge Todd P. Wolf. By Gretchen Schuldt Trequelle T. Vann-Marcouex, who turned 18 in April, was facing serious charges when he appeared before Wood County Circuit Judge Todd P. Wolf on Aug. 14 for a preliminary hearing. Vann-Marcouex was facing a maximum of 65 years in prison for allegedly participating in an armed home invasion and robbery. Vann-Marcouex denied involvement in the crime. He had been in jail for at least 11 days, and he still did not have a lawyer. He qualified for representation by the State Public Defender's Office (SPD), which provides lawyers for very low-income defendants. A lawyer from that office represented him during his initial appearance, where bail was set at $25,000, but no one had been appointed to handle his case after that. “I have been calling the Public Defender’s Office every single day, and they make it – I get on the phone with them, and they’d laugh,” Vann-Marcouex said at the end of the preliminary hearing, according to a transcript of the proceeding. “When I called them yesterday and I asked them how is it I don’t have a public defender and I got my court in less than 24 hours, and she is, like, right. How is that an answer, right? How is that an answer?” “Well, you have to deal with them on that,” Wolf responded. “I can only do the hearings that are before me.” Wolf also did not appoint a lawyer for Vann-Marcouex, either, even though he should have done so. "I don't understand how this is enough evidence," Vann-Marcouex said after Wolf bound him over for trial. "Okay," the judge responded. "That will be something you can discuss with your attorney." Vann-Marcouex hanged himself in the jail that night. It was the fifth suicide in two years in the Wood County Jail. SPD spokesman Randy Kraft said the office did not take Vann-Marcouex's case because of a direct conflict of interest and so had to appoint a private bar attorney to take the case. "Agency staff made approximately 300 calls and emails to private attorneys certified to take SPD cases before an appointment was ultimately made on Aug. 14," Kraft said in an email. "The Order Appointing Counsel was filed with the court on the same day. "In cases in our more rural counties, the difficulty in locating a private bar attorney is fairly typical," Kraft said. "What is less typical, however, is the court proceeding with a preliminary hearing without the benefit of an attorney. Defendants benefit from having an attorney with them in court. Attorneys not only have the skills necessary to protect the rights of their clients, but they are also able to guide them through the criminal justice system." The Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees defendants in criminal cases the right to effective counsel. The Wisconsin Supreme Court has specifically ruled that defendants are entitled to counsel at preliminary hearings. But Vann-Marcouex, who had never been in serious trouble before, was unrepresented as a prosecutor described the state’s case against him. When he did try to talk, the judge cut him off. It is impossible to draw a line directly from the young man's lack of representation to his suicide, but a lawyer could have helped Vann-Marcouex deal with the overwhelmingly stressful situation he faced, said Chad Lanning, president of the Wisconsin Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. A lawyer can put things in context and "give them that hope that all is not lost," he said. Law enforcement may presume defendants are guilty and treat them that way, or frighten them with worst-case predictions in attempts to scare them straight. While court and law enforcement officials often emphasize the maximum penalties a defendant faces, a lawyer can give them a more realistic, less dire picture and explain legal defenses and a basic strategy of how they will unfold as the case moves forward. Vann-Marcouex wanted a lawyer. He just didn't get one, a fact acknowledged by the prosecution. "I did have a brief off-the-record conversation with Mr. Vann-Marcouex," Assistant District Attorney Leigh Neville-Neil said at the beginning of the preliminary hearing, according to the transcript. "He indicated he applied and qualified for a Public Defender. He has been calling them repeatedly and has not been assigned counsel yet, just so the Court's aware." "Okay," Wolf responded. "That's my understanding, Mr. Vann-Marcouex, though, in fact, what the Court is required to do by law is to have this preliminary hearing done within 10 days when someone's in custody on a cash bond, such as yourself." Wolf did not raise the possibility of a court-appointed attorney, nor did Neville-Neil, who is now on leave. Wolf declined to answer written questions from WJI. Wood County District Attorney Craig Lambert did not respond to written questions. "You do have the right to ask questions of the officer, although if you had an attorney here, they would tell you not to do so . ..." – Circuit Judge Todd P. Wolf The lack of legal representation for defendants in criminal cases who cannot afford to hire a lawyer is creating a constitutional crisis in the state. The SPD appoints private bar attorneys to handle cases when it cannot do so because of excessive caseloads or potential conflicts of interest. The low pay the office can offer – $40 an hour, the lowest rate in the nation and not enough to cover the average lawyer's overhead costs – means more and more lawyers are turning down cases. The State Supreme Court earlier this year refused a request to increase the rate.

Judges are supposed to appoint lawyers at county expense at $70 per hour if no other lawyer is available. “If lawyers are unavailable or unwilling to represent indigent clients at the SPD rate of $40/hour, as is increasingly the case, then judges must appoint a lawyer under SCR 81.02, at county expense,” the State Supreme Court said in its order declining to increase the $40 rate. Wolf instead explained that the state would outline its evidence to show probable cause that Vann-Marcouex committed the three crimes with which he was charged: armed robbery, burglary, and child abuse (a 17-year-old was struck with a gun during the home robbery). Prosecutors "have to introduce that type of evidence so I feel comfortable enough that the case can proceed with that probable cause finding, so I am going to go through and hear the evidence here today just to see if it meets that standard," he said, according to the transcript. "If it doesn't, the case would get dismissed. If it does, you are in no different position than you were in when you walked in here. ..." Wolf continued: "You do have the right to ask questions of the officer, although if you had an attorney here, they would tell you not to do so because anything you say is being recorded here today on the record and could be used against you, and you clearly wouldn't want to give up your right for self-incrimination by making some statements that could be used against you. Do you understand that then, sir? Do you understand that." "Yeah," Vann-Marcouex replied. After Neville-Neil finished questioning an investigating officer, Wolf told Vann-Marcouex he could ask questions, "but again, realize anything you are saying is being taken down and could be used against you." Later, the judge told Vann-Marcouex that he had a right to present evidence, but "I have to make a decision in the light most favorable to the state, and obviously you'd be giving up any right to self-incrimination if you did so. Do you wish to present any evidence?” "I mean, I was watching my nephew that night," Vann-Marcouex said. "My sister isn't here right now, I don't see her, but, um –" The judge cut him off. "You have to present evidence through testimony here, not make an argument, but no attorney would tell you to do that with each of the charges you are facing here because, again, I have to do it in the light most favorable to the State, all right? Do you wish to present anything now or not?" Wolf said. Vann-Marcouex shook his head. That was his last court appearance. It was the same day he got his lawyer. That same night, jail staff found him in his cell, where he apparently tried to hang himself. He died a few days later. Margo Kirchner contributed to this story. By Margo Kirchner The lawsuit brought by the estate of the man who died in the back seat of a squad car after repeatedly complaining that he could not breathe may face months of delay as the case bounces between the federal trial and appellate courts, thanks to an opinion last week by the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals. Derek Williams Jr. died in the back seat of a Milwaukee Police Department squad car on July 6, 2011. Officers failed to call for medical help for Williams until after he collapsed and stopped breathing. By then he could not be revived. In July 2016, Williams’ estate and three children sued 10 officers for failing to attend to Williams’ medical needs while in custody and for wrongful death. The plaintiffs also sued the City of Milwaukee, claiming that its unwritten policies and practices caused Williams’ death. U.S. District Judge J.P. Stadtmueller held in August 2017 that the case should go to trial. He rejected the officers’ summary judgment motion, which argued that the qualified immunity doctrine bars suit against them. Under long-time U.S. Supreme Court case law, qualified immunity protects public officials from civil liability unless their conduct violated a clearly established constitutional right that a reasonable person would have known. The doctrine balances the need to hold public officials accountable when they act irresponsibly with the need to shield them from liability when they perform their duties reasonably. The officers appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. That court ruled last week that it could not decide the officers’ appeal because Stadtmueller failed to analyze qualified immunity for each officer individually; his decision addressed their actions as a group. The appeals court remanded for further review by Stadtmueller, setting up another opportunity for the officers to appeal if Stadtmueller again rules against them. Friday’s appellate opinion was issued about 13 months after Stadtmueller’s initial ruling. Statistics available on the U.S. Courts’ website peg the median length of an appeal in the Seventh Circuit at eight months. Senior U.S. District Judge Robert W. Gettleman of the Northern District of Illinois, sitting as a guest on the Seventh Circuit panel, authored the appellate opinion, joined by Seventh Circuit Judge Joel M. Flaum. Seventh Circuit Senior Judge Kenneth F. Ripple agreed that Stadtmueller did not properly consider each officer individually but dissented on other grounds. Because of the summary-judgment stage of the case, all disputed facts were taken in the plaintiffs’ favor. Plaintiffs’ evidence showed that shortly after midnight on July 6, 2011, Williams was walking north on Holton Street in Milwaukee. He wore a mask and held a cell phone under his clothing, making him appear armed. Four officers in two squad cars noticed Williams as he approached a couple from behind and believed they were witnessing an attempted armed robbery. When one squad car stopped, Williams ran. An officer chased Williams on foot while both cars followed, and additional officers responded to the scene. Williams was a 22-year-old African-American male in good physical shape. He ran 200 to 300 yards and jumped over a fence. After about eight minutes officers found him in a back yard; both Williams and the chasing officer were breathing heavily. After a brief struggle, two officers pulled Williams down onto his back and flipped him over to apply handcuffs, with one officer kneeling on Williams’ back. Williams said he could not breathe, at which point the officer lifted some of his weight off of Williams. A recorded radio call of an officer telling dispatch that Williams was in custody captured Williams complaining that he could not breathe. Williams went limp as officers lifted him up. Williams was unresponsive, breathing heavily, and sweating, but the officers thought he was faking any distress. After they used a painful procedure to determine consciousness, Williams opened his eyes and told the officers that the two alleged victims were his friends and he was “just playing around” with them. Williams again complained about not being able to breathe. Neighbors heard his complaints and heard an officer tell Williams to “shut up.” After five minutes the officers moved Williams to the front yard, where he went limp again and had to be dragged. Officers told him to stop “playing games” but Williams again said he could not breathe. A neighbor heard Williams say he could not breathe while officers cursed at him. Another neighbor called 911 but was told that paramedics would not be sent unless officers called for them. Friday’s appellate opinion was issued about 13 months after Stadtmueller’s initial ruling. Statistics available on the U.S. Courts’ website peg the median length of an appeal in the Seventh Circuit at eight months The arresting officers placed Williams in the rear seat of a squad car but did not discuss Williams’ condition. Although the officer sitting in the driver’s seat turned on a back-seat video recorder, he failed to activate a feed to observe Williams on his computer screen. Nor did he turn to look at Williams.

Williams again said he could not breathe, that he was dying, and that he needed an ambulance, but the squad officer told Williams he was “breathing just fine” and “playing games.” Nevertheless, the officer rolled down the window and turned on the air conditioner. A witness saw Williams rocking around in the back seat and heard him say he could not breathe. According to the Seventh Circuit, the recording of Williams in the back seat “shows him in obvious distress, eventually collapsing onto the door of the car.” The squad officer was replaced with another, but the two did not discuss Williams’ breathing complaints and the video feed remained off. When the second squad officer turned to look at the back seat, Williams was slumped over. The officer checked Williams and found no pulse or breath, but he did not call for medical assistance. Instead, he unsuccessfully looked for help at another squad car and then radioed other officers. Finally, a responding officer called for medical help approximately 12 minutes after Williams was placed in the car and three minutes after he was found motionless. An officer began CPR and paramedics took over, but Williams was declared dead at 1:41 a.m. The Milwaukee County Medical Examiner determined the cause of death as sickle-cell crisis triggered by Williams’ flight from and altercation with police, though another medical expert said the cause of death is indeterminable. As noted by the Seventh Circuit in its opinion, qualified immunity does not protect a public official from suit when (1) the official violated a constitutional right and (2) that right was clearly established at the time of the challenged conduct. Plaintiffs claim that the defendant officers violated Williams’ Fourth Amendment right to receive reasonable medical care while in custody. The officers conceded that calling an ambulance would not have compromised any police interest or been burdensome. Therefore, the Seventh Circuit stated in its opinion, to establish the constitutional violation the plaintiffs had to show only that the officers had notice of Williams’ medical need and that the medical need was serious. Stadtmueller found that plaintiffs presented such evidence. Further, Stadtmueller found that an arrestee’s right to objectively reasonable medical attention was clearly established by at least 2007. The Seventh Circuit, however, said that Stadtmueller improperly grouped the actions of the officers together when he assessed the case. According to the court, “each defendant-officer had a different degree of contact with Williams and had different assigned responsibilities with respect to the apprehension of Williams and investigation of the alleged armed robbery. Although the district court’s recitation of facts acknowledges the officers’ varying encounters with Williams, its qualified-immunity analysis lacks any individualized assessment.” The court remanded, directing Stadtmueller to articulate his qualified immunity analysis officer by officer. Only then, said the Seventh Circuit, can it review the officers’ appeal. Trial was previously scheduled for late August 2017 but postponed due to the appeal. The claims against the city were not part of the appeal and remain pending for trial. It is unclear how much delay this do-over will cause. District courts generally cannot act on a remand until receipt of a document called a “mandate,” which often issues a few weeks after an opinion. Stadtmueller could act quickly, without additional briefing, but if he rules that any individual defendant is not protected by qualified immunity, that defendant could appeal again.  Ripple Ripple By Margo Kirchner The recent challenge to Wisconsin’s "cocaine mom" statute that allows pregnant women to be locked up failed this week because the plaintiff moved out of state. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit ordered Tamara Loertscher’s challenge dismissed because she no longer is subject to the Wisconsin law and therefore cannot challenge its constitutionality. Loertscher was jailed without a lawyer after she told hospital staff that before learning of her pregnancy she used marijuana and methamphetamines to deal with medically induced depression and fatigue. Loertscher lived in Wisconsin when she filed her case in late 2014. She later moved out of state. U.S. District Judge James Peterson found that the move did not impact Loertscher’s claims and held the "cocaine mom" law unconstitutional for failing to give women fair warning about what conduct is prohibited and failing to provide authorities any meaningful standard for enforcement. Peterson blocked the law, but the U.S. Supreme Court stayed that order while Wisconsin Attorney General Brad Schimel appealed to the Seventh Circuit. The appeals court, in a decision written by Senior Circuit Judge Kenneth F. Ripple, vacated Peterson’s order, but not based on the merits of Loertscher’s challenge. Instead, the Seventh Circuit disagreed with Peterson about the impact of Loertscher’s move. The court pointed to a constitutional provision limiting federal courts to deciding “actual, ongoing controversies.” The existence of a controversy when a case is filed is not enough; the issue must remain live and the parties must retain a personal interest in the outcome throughout the case, even on appeal. Because Loertscher moved out of state during the case she no longer needs protection from the law, said the court. And in cases seeking to block enforcement of a statute, “once the threat of the act sought to be enjoined dissipates, the suit must be dismissed as moot.” Ripple was joined in his opinion by Circuit Judges Joel M. Flaum and Daniel A. Manion. The panel noted the lack of any evidence showing that Loertscher moved due to the statute or fear of its application to her. According to the court, Loertscher’s case did not fall into a limited exception to the mootness rule for cases that are “capable of repetition, yet evading review.” The exception applies in rare situations when (1) a challenged action is too short to be fully litigated prior to its cessation and (2) a reasonable expectation exists that the same complaining party will be subject to the action again. In Roe v. Wade the Supreme Court said that pregnancy is a classic justification for the exception. But the Seventh Circuit found that Loertscher cannot satisfy the second part of the exception because her voluntary and permanent departure from Wisconsin “makes the possibility of her once again being subject to the statute a matter of pure speculation.” Loertscher has no reasonable expectation that she will find herself within Wisconsin’s borders when she is both pregnant and using drugs, the panel said. The court likened Loertscher’s case to that of two doctors who challenged Michigan’s physician-assisted suicide ban. The Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed the doctors’ case as moot when one doctor retired and the other moved from Michigan to California. Her voluntary departure from the state “makes the possibility of her once again being subject to the statute a matter of pure speculation.” WJI reported details of Loertscher’s case and the "cocaine mom" law previously. After Loertscher acknowledged her past drug use to hospital staff, the hospital reported Loertscher to the Taylor County Department of Human Services, claiming that her behavior with drugs put her fetus in serious danger. Taylor County appointed a lawyer to represent Loertscher’s fetus (but not Loertscher) and began proceedings under the "cocaine mom" law to determine whether Loertscher’s fetus needed protection or services.

Loertscher refused to participate in a quickly scheduled temporary physical custody hearing unless she had legal representation. The court conducted the hearing without her and ordered that she submit to an assessment and possible treatment for drug abuse. When Loertscher refused to comply with the order, the court held her in contempt and in jail for 18 days, during which time Loertscher received no prenatal care even after asking to see a doctor. Loertscher on her own contacted an attorney and secured appointment of a public defender. She obtained release only after agreeing to an alcohol and drug-abuse assessment and weekly drug testing at her own expense. All tests were negative and Loertscher delivered a healthy baby in January 2015. While pregnant, Loertscher sued the state, alleging that the "cocaine mom" law is unconstitutional and cannot be enforced. Judge Peterson agreed on the merits, but his decision no longer has any effect after the Seventh Circuit’s decision on appeal. Loertscher’s suit is the second unsuccessful attempt to overturn the law through litigation. A prior plaintiff also lost her case on procedural grounds.  Chemerinsky Chemerinsky By Margo Kirchner President Trump's next U.S. Supreme Court appointment likely would make Chief Justice John Roberts the ideological middle of the court, according to the dean of the University of California, Berkeley, Law School. Dean Erwin Chemerinsky noted that Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Anthony Kennedy, and Stephen Breyer are all older than the average age at which past Supreme Court justices have retired. Roberts becoming the "center" would show the Court's continued movement toward the conservative viewpoint, he said. Chemerinsky, a well-known scholar on constitutional law, spoke as part of a panel hosted by the American Constitution Society. He discussed the progression of the median or swing justice from Justice Lewis Powell to Justice Sandra Day O’Connor to Justice Anthony Kennedy. He said another Trump appointment would most likely have an effect on affirmative action laws, criminal penalties, and the exclusionary rule (which generally prohibits the admission of illegally obtained evidence). In addition, he sees five votes to overrule Roe v. Wade should another Trump appointee make it to the Court. He also expects, however, that if Democrats take the Senate in November 2018 they would sit on any Trump Supreme Court nominee until after the 2020 elections, as pushback after President Barack Obama’s failed Merrick Garland nomination. Senate Republicans refused to vote on Garland's nomination for 10 months, until Obama's term expired.

Law professors Melissa Murray and Pamela Karlan joined Chemerinsky on the panel, moderated by Caroline Frederickson, president of the American Constitution Society. Murray, a professor and faculty director of the Center on Reproductive Rights and Justice at Berkeley Law School, discussed a second Trump appointee’s potential effect on reproductive rights and the frequent chipping-away of Roe. Karlan, a professor at Stanford Law School, speculated on the status of LGBTQ rights if another Trump nominee joins the Court. Karlan noted the importance of getting the public to understand how court decisions affect their lives. |

Donate

Help WJI advocate for justice in Wisconsin

|

Copyright © 2024 Wisconsin Justice Initiative Inc.

The Wisconsin Justice Initiative Inc. does not endorse candidates for political office. The Wisconsin Justice Initiative Inc. is a 501(c)3 organization.

The Wisconsin Justice Initiative Inc. does not endorse candidates for political office. The Wisconsin Justice Initiative Inc. is a 501(c)3 organization.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed