|

Note: We are breaking our own rules again. WJI's "SCOW docket" pieces generally include decisions, dissents and concurrences all in one post. This time, with this case, we are doing it in four: First the lead decision, then the dissent, and then, in two separate posts due to length, the three concurrences. Why? Because this package of writings is significant and gives insight into how SCOW's seven justices think. And instead of allowing each writing justice 10 paragraphs, we are allowing up to 20. We also added a section on standing and other threshold issues. Other than that, the rules remain pretty much the same. The "Upshot," "Background" and, in this case, "Threshold issues" sections do not count as part of the 20 paragraphs because of their summary and very necessary nature. We've also removed citations from the opinion for ease of reading, but have linked to important cases and laws cited or information about them. Italics indicate WJI insertions except for case names, which also are italicized. The case: Richard Teigen and Richard Thom v. Wisconsin Elections Commission Majority/Lead Opinion: Justice Rebecca Grassl Bradley (52 pages), joined by Justice Patience D. Roggensack and Chief Justice Annette K. Ziegler; joined in part by Justice Brian Hagedorn Concurrence: Roggensack (14 pages) Concurrence: Rebecca Grassl Bradley (17 pages), joined by Roggensack and Ziegler Concurrence: Hagedorn (35 pages) Dissent: Justice Ann Walsh Bradley (18 pages), joined by Justices Rebecca F. Dallet and Jill J. Karofsky Intervenor defendant-appellants included the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee, Disability Rights Wisconsin, Wisconsin Faith Voices for Justice, and the League of Women Voters of Wisconsin.  Grassl Bradley Grassl Bradley The upshot Only the legislature may permit absentee voting via ballot drop boxes. WEC (Wisconsin Elections Commission) cannot. Ballot drop boxes appear nowhere in the detailed statutory system for absentee voting. WEC's authorization of ballot drop boxes was unlawful, and we therefore affirm the circuit court's declarations and permanent injunction of WEC's erroneous interpretations of law except to the extent its remedies required absentee voters to personally mail their ballots, an issue we do not decide at this time. ... Background During the pandemic spring of 2020, to accommodate the higher demand for absentee voting, WEC Administrator Meagan Wolfe issued a memo to local election officials. The memo states: "[Ballot] drop boxes can be used for voters to return ballots but clerks should ensure they are secure, can be monitored for security purposes, and should be regularly emptied." It also says, "[a] family member or another person may . . . return the [absentee] ballot on behalf of a voter." WEC's commissioners never voted to adopt this memo. A few months later, Administrator Wolfe and the assistant administrator issued the second document ("Memo two") ahead of the fall 2020 election. It encourages "creative solutions" to facilitate the use of ballot drop boxes. Specifically, Memo two informs municipal clerks that drop boxes can be "unstaffed," and states "[a]t a minimum, you should have a drop box at your primary municipal building, such as the village hall." WEC commissioners never voted on Memo two either. Municipal clerks acted on these memos. Administrator Wolfe avers she is aware of 528 ballot drop boxes utilized for the fall 2020 election. By the spring 2021 election, Administrator Wolfe says municipal clerks and local election officials reported 570 drop boxes, spanning 66 of Wisconsin's 72 counties. Teigen and Thom sued, challenging the legality of the drop boxes. Waukesha County Circuit Judge Michael Bohren issued an injunction prohibiting their use. The defendants appealed and the Supreme Court accepted the case, bypassing the Court of Appeals. Threshold issues The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee challenged the plaintiffs' standing in the case. Only Roggensack and Ziegler joined in Grassl Bradley's reasoning in rejecting the challenge, meaning that her lead opinion does not constitute a binding precedent on the question. DSCC argues the Wisconsin voters lack standing, asserting they "have not demonstrated 'a personal stake in the outcome of the controversy' separate and apart from the public at large, nor have they shown they have 'suffered or [are] threatened with an injury to an interest that is legally protectable.' " We reject this argument because the Wisconsin voters do have a "stake in the outcome" and are "affected by the issues in controversy." *** If the right to vote is to have any meaning at all, elections must be conducted according to law. Throughout history, tyrants have claimed electoral victory via elections conducted in violation of governing law. For example, Saddam Hussein was reportedly elected in 2002 by a unanimous vote of all eligible voters in Iraq (11,445,638 people). Examples of such corruption are replete in history. In the 21st century, North Korean leader Kim Jong-un was elected in 2014 with 100% of the vote while his father, Kim Jong-il, previously won 99.9% of the vote. Former President of Cuba, Raul Castro, won 99.4% of the vote in 2008 while Syrian President Bashar al-Assad was elected with 97.6% of the vote in 2007. Even if citizens of such nations are allowed to check a box on a ballot, they possess only a hollow right.* Their rulers derive their power from force and fraud, not the people's consent. By contrast, in Wisconsin elected officials "deriv[e] their just powers from the consent of the governed." The right to vote presupposes the rule of law governs elections. If elections are conducted outside of the law, the people have not conferred their consent on the government. Such elections are unlawful and their results are illegitimate. ... The Wisconsin voters' injury in fact is substantially more concrete than the "remote" injuries we have recognized as sufficient in the past. The record indicates hundreds of ballot drop boxes have been set up in past elections, prompted by the memos, and thousands of votes have been cast via this unlawful method, thereby directly harming the Wisconsin voters. The illegality of these drop boxes weakens the people's faith that the election produced an outcome reflective of their will. The Wisconsin voters, and all lawful voters, are injured when the institution charged with administering Wisconsin elections does not follow the law, leaving the results in question. *** Justice Brian Hagedorn disagrees with our standing analysis, proffering an alternative basis for standing divined from searching the penumbra of Wis. Stat. § 5.06. Although § 5.06 appears nowhere in the complaint and sets forth specific procedures that were never invoked, Justice Hagedorn concludes it nevertheless confers standing on the Wisconsin voters. It can't. Grassl Bradley, joined by Roggensack and Ziegler, also finds that the two voters did not first have to file their complaint with WEC and that the agency abandoned any sovereign immunity defense. Although WEC asserted in its answer that sovereign immunity barred "some" of the Wisconsin voters' claims, it did not say which ones. No reasonable judge could view WEC's briefing and answers at oral argument as maintaining a sovereign immunity defense. WEC's attorney even said at oral argument that WEC takes "no position" on the matter. *In a footnote, Grassl Bradley writes, "Justice Hagedorn seems to disagree, indicating the right to vote encompasses nothing more than the mere ability to cast a ballot. He fails to recognize that a lawful vote loses its operative effect if the election is not conducted in accordance with the rule of law." The guts

(Joined by Hagedorn, Roggensack and Ziegler) WEC's staff may have been trying to make voting as easy as possible during the pandemic, but whatever their motivations, WEC must follow Wisconsin statutes. Good intentions never override the law. *** Nothing in the statutory language detailing the procedures by which absentee ballots may be cast mentions drop boxes or anything like them. Wisconsin Stat. § 6.87(4)(b)1. provides, in relevant part, that absentee ballots "shall be mailed by the elector, or delivered in person, to the municipal clerk issuing the ballot or ballots." The prepositional phrase "to the municipal clerk" is key and must be given effect. ... An inanimate object, such as a ballot drop box, cannot be the municipal clerk. At a minimum, accordingly, dropping a ballot into an unattended drop box is not delivery "to the municipal clerk[.]" State law allows establishment of alternate absentee ballot sites, Grassl Bradley writes. Ballot drop boxes are not alternate absentee ballot sites because a voter can only return the voter's absentee ballot to a drop box, while an alternate site must also allow voters to request and vote absentee at the site. If a drop box were an alternate ballot site, by the plain language of the statute, "no function related to voting and return of absentee ballots that is to be conducted at the alternate site may be conducted in the office of the municipal clerk or board of election commissioners." Existing outside the statutory parameters for voting, drop boxes are a novel creation of executive branch officials, not the legislature. The legislature enacted a detailed statutory construct for alternate sites. In contrast, the details of the drop box scheme are found nowhere in the statutes, but only in memos prepared by WEC staff, who did not cite any statutes whatsoever to support their invention. Wisconsin Stat. § 6.855 identifies the sites at which in person absentee voting may be accomplished—either "the office of the municipal clerk" or "an alternate site" but not both. "An alternate site" serves as a replacement for "the office of the municipal clerk" rather than an additional site for absentee voting. Wisconsin Stat. § 6.87(4)(b)1. requires the elector to mail the absentee ballot or deliver it in person, "to the municipal clerk," which is defined to include "authorized representatives." This subparagraph contemplates only two ways to vote absentee: by mail and at "the office of the municipal clerk" or "an alternate site" as statutorily described. No third option exists. *** The defendants contend "to the municipal clerk" encompasses unstaffed drop boxes maintained by the municipal clerk. A hyper-literal interpretation of this prepositional phrase, taken out of context, would permit voters to mail or personally deliver absentee ballots to the personal residence of the municipal clerk or even hand the municipal clerk absentee ballots at the grocery store. "Municipal clerk," however, denotes a public office, held by a public official acting in an official capacity when performing statutory duties such as accepting ballots. The statutes do not authorize the municipal clerk to perform any official duties related to the acceptance of ballots at any location beyond those statutorily prescribed.

0 Comments

Note: We are crunching Supreme Court of Wisconsin decisions down to size. The rule for this is that no justice gets more than 10 paragraphs as written in the actual decision. The "upshot" and "background" sections do not count as part of the 10 paragraphs because of their summary and very necessary nature. We've also removed citations from the opinion for ease of reading, but have linked to important cases cited or information about them. Italics indicate WJI insertions except for case names, which also are italicized. Underlined text indicates emphasis added by the justices, not WJI. The case: Friends of Frame Park v. City of Waukesha Majority/Lead: Justice Brian Hagedorn (25 pages), joined in various parts by Justices Rebecca Grassl Bradley, Patience D. Roggensack, and Annette K. Ziegler. Concurrence: Grassl Bradley (43 pages), joined by Roggensack and Ziegler. Dissent: Justice Jill J. Karofsky (22 pages), joined by Justices Ann Walsh Bradley and Rebecca F. Dallet.  Hagedorn Hagedorn The upshot When ascertaining if a records requester is entitled to attorney's fees as a part of a mandamus action under the state's public records law, a party must "prevail[] in whole or in substantial part," which means the party must obtain a judicially sanctioned change in the parties' legal relationship. With respect to the mandamus action before us, the City properly applied the balancing test when it decided to temporarily withhold access to the draft contract in response to Friends' open records request. Accordingly, regardless of whether Friends may pursue fees after voluntary delivery of the requested record, Friends cannot prevail in its mandamus action and is not entitled to attorney's fees. Background Friends of Frame Park, a citizens' group, in October 2017 requested information about the city's plan to bring baseball to Waukesha and to Frame Park. The city rejected a request for a copy of the proposed contract with Big Top Baseball, saying it was still in negotiation and the city wanted to protect its bargaining position. The city said it would release the proposed contract after the Common Council took action on it. The contract was on the Common Council agenda for Dec. 19, 2017. Friends sued on the day before the meeting for release of the records. The following evening, the City's Common Council met. It is unclear from the meeting minutes whether, or to what extent, the draft contract was discussed. The minutes note the following with respect to Frame Park: "Citizen speakers registering comments against baseball at Frame Park"; the "City Administrator's Report" included a "Northwoods Baseball League Update"; and an "item for next Common Council Meeting under New Business" was to, "Create an ADHOC Committee for the purpose to address Frame Park and Frame Park issues." The city released the requested records on Dec. 20, even though the council had not voted on the contract. Consistent with its explanation initially denying release, the City explained the documents "are being released now because there is no longer any need to protect the City's negotiating and bargaining position." Friends then amended its complaint, asking the circuit court to hold that the City improperly withheld the draft contract. In advance of trial, the City filed a motion for summary judgment which the circuit court granted; Friends did not move for summary judgment. ... Friends appealed, and the Court of Appeals reversed the lower court decision. The city appealed to SCOW. The guts Four justices agree that to "prevail[] in whole or in substantial part" means the party must obtain a judicially sanctioned change in the parties' legal relationship. Accordingly, a majority of the court adopts this principle. This conclusion arguably raises other statutory questions. Prior court of appeals cases have held that a requester could still pursue attorney's fees even if the records have been voluntarily turned over. This conclusion rested on its causation-based theory, however. The concurrence argues that under the proper statutory test we announce today, a mandamus action becomes moot after voluntary compliance, and record requesters have no separate authority to pursue attorney's fees. We save this issue for another day. Even if record requesters can pursue attorney's fees following release of the requested records, an award of fees would not be appropriate here. This is so because in temporarily withholding the draft contract, the City complied with the public records law. Applying the balancing test, the City pointed to the strong public interest in nondisclosure – namely, protecting the City's negotiating and bargaining position and safeguarding the Common Council's prerogative in contract approval. These considerations outweigh the strong public policy in favor of disclosure. Furthermore, the City recognized the balance of interests would shift after the Common Council meeting, and it properly disclosed the draft contract at that time. Therefore, the City did not violate the public records law. And thus, the requester did not and could not prevail in whole or substantial part in this action. Therefore, no judicially sanctioned change in the parties' relationship is appropriate and the requester is not entitled to any attorney's fees. *** Section 19.37 of the state statutes provides that the record requester may be entitled to various damages and fees as a result of the mandamus action. Relevant to this case, the statute contains the following fee-shifting provision: "Except as provided in this paragraph, the court shall award reasonable attorney fees, damages of not less than $100, and other actual costs to the requestor if the requester prevails in whole or in substantial part in any action filed under sub. (1) relating to access to a record or part of a record. ..." Besides attorney's fees, the law also specifies that the circuit court shall award actual damages if "the authority acted in a willful or intentional manner" and may award punitive damages if the authority "arbitrarily and capriciously denied or delayed response to a request or charged excessive fees." The fee-shifting provision was comparable to one contained in the federal Freedom of Information Act, Hagedorn said. A federal appeals court ruled that damages could be awarded if records were released prior to the conclusion of a FOIA case if bringing the case caused the records to be released. In 2001, however, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected that reasoning. It expressly rejected ... the causation-based interpretation, concluding instead that "the term 'prevailing party' " refers to "one who has been awarded some relief by the court." Congress eventually adopted a law restoring the causation provision. The Wisconsin Legislature has not specifically embraced causation-based awards, Hagedorn said. When the legislature uses a legal term of art with a broadly accepted meaning – as it has here with "prevails" ... we generally assume the legislature meant the same thing. If the idea that a party could prevail in a lawsuit in the absence of court action was unknown in Wisconsin when this statute was adopted, we should not read that interpretation into the statute now given the absence of any evidence that it was understood to have that meaning when enacted. A causation or catalyst theory is not a comfortable fit with statutory text that allows recovery of attorney's fees "if the requester prevails in whole or in substantial part in any action." The better course is to follow the United States Supreme Court's lead and return to a textually-rooted understanding of when a party prevails in a lawsuit. Absent a judicially sanctioned change in the parties' legal relationship, attorney's fees are not recoverable. ... Without a causation-based theory governing the meaning of prevailing party under the statute, however, it is unclear whether voluntary compliance following the filing of a lawsuit could still allow a requester to pursue fees. We reserve this question for another day. Even if attorney's fees may be awarded after the voluntary production of records, the City here did not violate the law, as explained below. Friends therefore would not be entitled to any judicial relief – that is, it would not prevail in whole or substantial part – even if fees are available in this context. Accordingly, Friends is not entitled to attorney's fees either way. *** Invoking the language in Wis. Stat. § 19.85(1)(e) (exemptions to open meetings requirements) the City explained that "the contract [was] still in negotiation with Big Top." Withholding disclosure was important to "protect the City's negotiation and bargaining position" and "the City's ability to negotiate the best deal for the taxpayers." Disclosure "would substantially diminish the City's ability to negotiate different terms the Council may desire for the benefit [of] the City" and "compromise[]" "the City's negotiating and bargaining position." The City further explained that the "draft contract is subject to review, revision, and approval of the Common Council before it can be finalized, and the Common Council [has] not yet had an opportunity to review and discuss the draft contract." The City indicated it would disclose the draft contract after the Common Council had taken action. The circuit court correctly concluded the reasons set forth in the City's letter supported temporarily withholding the draft contract. Without question, the public interest in matters of municipal spending and development is significant. There is good reason for the public to know how government spends public money. This ensures citizen involvement and accountability for public funds. However, contract negotiation often requires a different calculus. Wisconsin ... law identifies the public interest in protecting a government's "competitive or bargaining" position in adversarial negotiation. It is not uncommon for the state or local municipalities to negotiate certain contracts in private, especially in competitive business environments. ... Under these circumstances, the City's interest in withholding the draft contract to protect its bargaining position until the Common Council had the opportunity to consider the contract outweighed the public's interest in immediate release. The City properly applied the balancing test and did not violate the public records law by temporarily withholding the draft contract, nor did it delay release of the contract unreasonably. Accordingly, regardless of whether the issue of attorney's fees is moot, Friends is not entitled to attorney's fees because it did not prevail in whole or in substantial part on the merits of its mandamus action.  Grassl Bradley Grassl Bradley Concurrence The court of appeals has repeatedly failed to give the legal term of art in statute its accepted legal meaning. In at least six cases, the court of appeals has instead endorsed the now-defunct "catalyst theory," under which a party may be deemed to have prevailed – even in the absence of favorable relief from a court – if the lawsuit achieved at least some of the party's desired results by causing a voluntary change in the defendant's conduct. In this case, the court of appeals erred in applying ... precedents, embracing a purposivist and consequentialist approach to statutory interpretation, in derogation of the textualist approach Wisconsin courts are bound to follow. I write separately because the majority/lead opinion does not acknowledge this case is moot, obviating any need to address the merits. All records were given to the requester before the circuit court ever rendered a decision. ... In this case, the act requested had already been performed, so neither the circuit court nor the court of appeals nor this court needed to address the merits of Friends' public records claim. Because this case is moot, we need not consider whether Friends is entitled to relief. Without favorable relief, Friends cannot recover attorney fees. Because the majority/lead opinion reaches the merits of this case without any explanation of what possible favorable relief could be granted, I respectfully concur. After the public records statute damages section was enacted in 1982, the court of appeals adopted the catalyst theory, which conflicts with the longstanding meaning of what it means to prevail in a court case. A "fair reading" of a statute requires adherence to the statute's text as it was understood at the time of the statute's enactment. The SCOW docket: When "at the driveway" means "in the street near the end of the driveway"6/22/2022 Note: We are crunching Supreme Court of Wisconsin decisions down to size. The rule for this is that no justice gets more than 10 paragraphs as written in the actual decision. The "upshot" and "background" sections do not count as part of the 10 paragraphs because of their summary and very necessary nature. We've also removed citations and footnotes from the opinion for ease of reading, but have linked to important cases cited or information about them. Italics indicate WJI insertions except for case names, which also are italicized. The case: State of Wisconsin v. Valiant M. Green Majority opinion: Justice Brian Hagedorn (7 pages), joined by Chief Justice Annette K. Ziegler and Justices Patience D. Roggensack, Rebecca Grassl Bradley, Rebecca F. Dallet, and Jill J. Karofsky Dissent: Justice Ann Walsh Bradley (11 pages)  Hagedorn Hagedorn The upshot The Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution provides in relevant part: "no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation . . . ." After Valiant M. Green was arrested for operating while intoxicated (OWI), law enforcement obtained a warrant to draw his blood. Green now argues the facts supporting that warrant were insufficient to find probable cause. We disagree. Background Here, the circuit court issued a search warrant to draw Green's blood based on the affidavit of Kenosha Police Officer Mark Poffenberger. The affidavit took the form of a pre-printed document with blank spaces and check-boxes that Officer Poffenberger completed. It stated that around 1:19 p.m. on May 25, 2014, Green "drove or operated a motor vehicle at driveway of [Green's home address]" — the underlined portion being part of the preprinted form, and the remainder Officer Poffenberger's handwritten addition. Several checked boxes provided additional facts. First, Green was arrested for the offense of "Driving or Operating a Motor Vehicle While Impaired as a Second or Subsequent Offense, contrary to chapter 346 Wis.Stats." Second, Green "was observed to drive/operate the vehicle by" both "a police officer" and "a citizen witness," whose name was written in by Officer Poffenberger. A third checked box was labeled "basis for the stop of the arrestee's vehicle was," and Officer Poffenberger supplied "citizen statement" by hand. The affidavit also described Green's statements and the officer's observations. According to Officer Poffenberger's handwritten note, Green "admitted to drinking alcohol at the house." And Officer Poffenberger checked several boxes noting that when he made contact with Green, he observed a strong odor of intoxicants, red/pink and glassy eyes, an uncooperative attitude, slurred speech, and an unsteady balance. Finally, Officer Poffenberger checked boxes indicating that Green refused to perform field sobriety tests, refused to submit to a preliminary breath test, and was "read the 'Informing the Accused' Statement . . . and has refused to submit to the chemical test requested by the police officer." After the warrant issued, medical staff drew Green's blood. It revealed a blood alcohol level of 0.214 g/100 mL, an amount well above the legal limit. The State charged Green with fourth offense OWI, fourth offense operating with a prohibited alcohol concentration (PAC), and resisting an officer. Green moved to suppress the results of the blood draw on the grounds that the warrant was deficient. The circuit court denied the motion. It concluded that even if the court erroneously issued the warrant (the court thought it had), the error did not merit suppression. At trial, the jury found Green guilty of OWI and PAC. The circuit court granted the State's motion to dismiss the OWI count and entered judgment against Green on the PAC count. The court of appeals summarily affirmed, holding the circuit court properly issued the warrant in the first place. We granted Green's petition for review. The guts When we examine whether a warrant issued with probable cause, we review the record that was before the warrant-issuing judge. Specifically, we look at the affidavits supporting the warrant application and all reasonable inferences that may be drawn from the facts presented. However, our review is not independent; we defer to the warrant-issuing judge's determination "unless the defendant establishes that the facts are clearly insufficient to support a probable cause finding." Probable cause exists where, after examining all the facts and inferences drawn from the affidavits, "there is a fair probability that contraband or evidence of a crime will be found in a particular place." *** Before us, Green continues to argue the warrant was issued without probable cause. He focuses not on the indicia of intoxication, but the location where he operated his vehicle. Green's main argument is that the handwritten word "driveway" on the form alleges only that he drove within the confines of his driveway. This matters because the statute criminalizing OWI and PAC offenses — Wis. Stat. § 346.63(1)(a), (1)(b) — does "not apply to private parking areas at . . . single-family residences." Rather, the laws apply "upon highways" and "premises held out to the public for use of their motor vehicles." Green's driveway is not a highway nor is it a (sic) held out to the public for motor vehicle use. Thus, because Green would not have committed an OWI or PAC by operating his vehicle on his driveway, Green contends the affidavit alleged only noncriminal activity and fell short of showing probable cause that any criminal activity occurred. Green's argument fails, however, because reasonable inferences from the affidavit support finding probable cause that Green drove on a public road. And that's all that is needed. "Probable cause is not a technical, legalistic concept but a flexible, common-sense measure of the plausibility of particular conclusions about human behavior." So when we examine a warrant application, the "test is not whether the inference drawn is the only reasonable inference." Rather, the "test is whether the inference drawn is a reasonable one." This warrant passes the test. Following the pre-printed word "at" is space for a location, which Officer Poffenberger identified as the driveway of Green's residential address. It is reasonable to read the officer's addition of the phrase "driveway of [residential address]" to refer to a specific location on the road, much like an intersection would provide a similarly specific location. The affidavit does not say Green's driving occurred merely in his driveway, but at his driveway — a location that can reasonably be read to refer to a position on the road adjacent to his driveway. Other portions of the affidavit are consistent with this reading. The affidavit points to two witnesses who observed Green "drive/operate the vehicle": a police officer and a named citizen witness. And the stop was occasioned by a citizen statement; someone besides the officer saw something that occasioned a call to the police. Viewing the entire affidavit together, a judge could reasonably infer that Green operated his vehicle on the road while intoxicated, not solely in his driveway. This "is not the only inference that can be drawn, but it is certainly a reasonable one." Examining the totality of the facts laid out in the affidavit, we conclude Green has not met his burden to show the affidavit was clearly insufficient to support a finding of probable cause. Accordingly, Green's challenge to the warrant and motion to suppress the evidence obtained thereby fails.  A.W. Bradley A.W. Bradley The dissent Confronted with the absence of probable cause here, the majority contrives to manufacture its presence. The affidavit in support of the warrant said that Green drove his car while intoxicated "at his driveway." But this isn't a crime. The law requires that one drive on a highway, and Green's private driveway obviously does not meet that requirement. In retrospect, even the warrant-issuing judge in this case acknowledged that the facts alleged in the affidavit in support of the search warrant did not amount to probable cause. He recognized that "I did make an error in not frankly asking the officer" for "more data." *** First, the majority errs by drawing several inferences from an affidavit that does not allege a crime has actually been committed. Wisconsin's OWI laws apply only to highways and "premises held out to the public for use of their motor vehicles." Such laws explicitly do not apply to "private parking areas" at single- family residences. *** Despite the fact that the OWI statutes apply only on highways and not private roads or driveways, the majority insists that the handwritten "driveway" could "refer to a specific location on the road, much like an intersection would provide a similarly specific location." But the affidavit did not say "at the intersection" or "on the road adjacent to the driveway." The majority would have us believe that "at the driveway" does not mean what it says. How can it be reasonable to infer that a crime has been committed when the only reasonable inference that can be drawn from the affidavit is that Green was operating a vehicle at his own driveway? The SCOW docket: Citing Marsy's Law, court OKs drugging pretrial defendants against their will5/25/2022 Note: We are crunching Supreme Court of Wisconsin decisions down to size. The rule for this is that no justice gets more than 10 paragraphs as written in the actual decision. The "upshot" and "background" sections do not count as part of the 10 paragraphs because of their summary and very necessary nature. We've also removed citations from the opinion for ease of reading, but have linked to important cases cited or information about them. Italics indicate WJI insertions except for case names, which also are italicized. The case: State of Wisconsin v. Joseph G. Green Majority opinion: Justice Patience D. Roggensack (24 pages), joined by Justices Rebecca Grassl Bradley, Brian Hagedorn, and Annette K. Ziegler; Justices Ann Walsh Bradley, Rebecca F. Dallet and Jill J. Karofsky joined in part Concurrence / dissent: Walsh Bradley (7 pages), joined by Dallet and Karofsky  Roggensack Roggensack The upshot We conclude that because the State's significant pretrial interests in bringing a defendant who meets each one of the factors set out in Sell v. United States to competency for trial and providing timely justice to victims outweigh upholding a defendant's liberty interest in refusing involuntary medication at the pretrial stage of criminal proceedings . . . (the) automatic stay of involuntary medication orders pending appeal does not apply to pretrial proceedings. Background On December 27, 2019, the State filed a criminal complaint charging Green with first-degree intentional homicide with use of a dangerous weapon. Pretrial, defense counsel raised reason to doubt Green's competency to proceed. The circuit court ordered a competency examination, which was completed by Dr. Craig Schoenecker and filed with the court. At the competency hearing, Dr. Schoenecker testified that Green was not competent but could be restored to competency through anti-psychotic-type medication within the 12-month statutory timeframe. ... After the hearing, the circuit court found Green incompetent. Accordingly, the court entered an order of commitment for treatment with the involuntary administration of medication. Following this determination, Green appealed and filed an emergency motion for stay of the involuntary medication order pending appeal, which was automatically granted by the circuit court pursuant to our decision in (State v) Scott. The State responded with motions to lift the automatic stay and to toll (pause) the statutory time period to bring a defendant to competence, both of which were granted by the circuit court. Green appealed. He moved for relief pending appeal, which included reinstatement of the temporary stay. The court of appeals reversed the circuit court's involuntary medication order and its order lifting the automatic stay of involuntary medication. In addition, the court of appeals determined that the circuit court lacked authority to toll the statutory time period to bring Green to competency. We granted the State's petition for review. Upon granting review, the parties submitted briefs addressing the circuit court's ability to toll the limits on the maximum length of commitment for competency restoration. However, following oral argument, additional briefing was ordered to answer whether the automatic stay required by Scott applied to pretrial proceedings. We determine: (1) whether Scott's automatic stay applies to pretrial competency proceedings and (2) whether Wis. Stat. § 971.14(5)(a)1. permits tolling the 12-month limitation provided to restore a defendant to competency. The guts

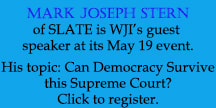

If a defendant is found to be incompetent, a court may allow the government to confine and involuntarily medicate the defendant if certain criteria are met. In Scott, the court ruled that involuntary medication orders are subject to an automatic stay pending appeal to preserve the defendant's 'significant' constitutionally protected 'liberty interest' in 'avoiding the unwanted administration of antipsychotic drugs.' In Sell, the Supreme Court set forth criteria for determining when the government may be allowed to involuntarily medicate a defendant for the purpose of making the defendant competent to stand trial. In short summation, a court must find that: (1) there are important government interests at stake, including bringing a defendant to trial for a serious crime; (2) involuntary medication will significantly further those state interests; (3) involuntary medication is substantially likely to render the defendant competent to stand trial; and (4) administration of the drugs is in the patient's best medical interest in light of his medical condition. However, postconviction circumstances that call for governmental involuntary medication are "rare." As with (a prior defendant's) concern in a postconviction context, significant, competing interests underlie our consideration of the involuntary administration of medication in a pretrial context. The defendant holds the same substantial liberty interest in refusing involuntary medication, regardless of the stage of proceedings. Once a defendant is subject to involuntary medication, irreparable harm could be done. On the other hand, the State has a significant interest in bringing a defendant to trial. The State's power "to bring an accused to trial is fundamental to a scheme of 'ordered liberty' and prerequisite to social justice and peace." Further, unlike postconviction proceedings, in pretrial proceedings, the State has yet to employ a significant portion of the criminal justice process to try to achieve justice and uphold the considerable victim and community interests at stake. For example, victims are guaranteed a right to "justice and due process," as well as a "timely disposition of the case, free from unreasonable delay." Wis. Const. art. I, § 9m(2)(d). The "unreasonable delay" phrase is part of the "Marsy's Law" amendment to the state constitution approved by voters last year. And while treatment to competency is not always necessary for postconviction proceedings, the State is required to bring a defendant to competency before a defendant can be tried. The terms of (state law) limit the treatment time for an incompetent defendant to "a period not to exceed 12 months, or the maximum sentence specified for the most serious offense with which the defendant is charged, whichever is less." As soon as a defendant is in custody for treatment, the statutory time during which he or she may be held before trial begins. *** If the State is unsuccessful at restoring competency for trial, the likelihood of which is increased if treatment is prevented by the automatic stay of Scott, a defendant must be discharged from commitment and released unless civil commitment proceedings are commenced. . . . Since our decision in Scott, the State has been trapped on both ends of the pretrial competency process. On one hand, (statute) permits a defendant to be held for 12 months to be brought to competence. On the other hand, Scott's automatic stay of the involuntary medication order keeps the State from starting the treatment that has been ordered by a court. While the State was given some leeway in the form of a modified Gudenschwager test, this is a high burden, and when employed, can use up the entire 12-month maximum commitment period that is permitted for treatment. And, if the State is not able to satisfy this Gudenschwager test and the time during which treatment can be required expires, the State is without recourse for prosecution. This is an unexpected consequence of the automatic stay that we created in Scott. Note: Hey, this one is a little different! WJI's "SCOW docket" pieces generally include decisions, dissents and concurrences all in one post. This time, with this case, we are doing it in three: First we shortcutted the decision, then the dissent, and now the concurrences. Why? Because this package of writings, and the strange U.S. Supreme Court decision that led to it, are extremely important to the state and country. Besides that, the SCOW decisions are unusually long – 142 pages, all in, not counting the cover sheets. And instead of allowing each writing justice 10 paragraphs, we are giving each 15. Other than that, the rules remain the same. We've removed citations from the opinion for ease of reading, but have linked to important cases cited or information about them. Italics indicate WJI insertions except for case names, which also are italicized. The case: Billie Johnson v. Wisconsin Elections Commission Concurrence: Justice Rebecca Grassl Bradley (49 pages), joined by Justices Patience D. Roggensack and Annette K. Ziegler Concurrence: Justice Brian Hagedorn (4 pages) Dissent: Justice Jill J. Karofsky (39 pages), joined by Justices Ann Walsh Bradley and Rebecca F. Dallet (See part 2) Majority opinion: Ziegler (50 pages), joined by Grassl Bradley, Hagedorn, and Roggensack (See part 1)  Grassl Bradley Grassl Bradley Grassl Bradley's concurrence This redistricting cycle proceeded in a manner heavily focused on color, supposedly for remedial purposes, but accomplishing nothing but racial animosity as showcased by the dissent's race-baiting rhetoric and condescension toward people of color. The United States Supreme Court rejected Homer Plessy's argument that racial segregation violates the Fourteenth Amendment, to its everlasting shame. Plessy exists in our nation's history as a stain, dishonoring America's quest for equality under the law for all, which began with the founding. At times, the United States has strayed from this sacred principle, often on the basis of sham social science of the day promoting the repugnant notion that people of different races would be better off if the law distinguished between them. Allowing social science to infect constitutional analysis inevitably "result[s] in grave abuses of individual rights and liberty." *** Judges can certainly consider whether a particular government action has had a disparate impact on minorities – our color-blind Constitution does not countenance ignoring incidents of discrimination. Under a color-blind approach, however, this court may not order a remedy that purports to address racial discrimination by discriminating on the basis of race. The Constitution prohibits this court from sorting people on the basis of their race. *** Imposing a race-based redistricting plan, without strong evidence of necessity, endorses the stereotype that people of the same race must think alike and must think differently than people of other races. Governor Evers' plan, adopted by this court on March 3, imposed "distinctions . . . based upon race and color alone," which is "the epitome of that arbitrariness and capriciousness constitutionally impermissive under our system of government." *** The inconclusive pseudo-science presented to this court fell far short of justifying race-based redistricting, as the majority opinion thoroughly explains. It amounted to little more than selectively-cited election data, which appears to have been researched only after-the-fact. That is to say, mapmakers seem to have used racial stereotypes, not legitimate social science, to heuristically draw maps that segregated people based on race. No such "shortcuts" are allowed for proponents of race-based redistricting as a remedy for past discrimination. The dissent's ambitious attempt to paint Milwaukee County as the Jim Crow-era South reflects "an effort to cast out Satan by Beelzebub." The dissent would remedy what it perceives as racial disparities by literally "draw[ing] lines between the white and the black" with no apparent recognition that doing so replaces one devil with another. *** The people have a "right to know" what happened this redistricting cycle. Unfortunately, media coverage on this case, like on so many others, has been skewed by partisan pundits disappointed in the "results." One media outlet went so far as to run a subheadline attacking the motives of the nation's highest court: "The justices [of the United States Supreme Court] are concerned that Wisconsin's legislative maps may give too much political power to Black people." Ian Millhiser, Black Voters Suffer Another Significant Loss in the Supreme Court, Vox (Mar. 23, 2022) https://www.vox.com/2022/3/23/22993107/supreme-court-wisconsinrace-gerrymander-voting-rights-act-legislature-electionscommission. Worse still, while accusing the justices of indulging an "inflammatory assumption," specifically, "[t]hat legislative maps with fewer Black-majority districts are often preferred to those that give more power to Black voters," the author made an inflammatory assumption of his own, seemingly designed to foster racial tension. See id.; see also Mark Joseph Stern, The Supreme Court's Astonishing, Inexplicable Blow to the Voting Rights Act in Wisconsin, Slate (Mar. 23, 2022), https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2022/03/supreme-court-voting-rights-shredder-wisconsin.html. *** Governor Evers' oddly shaped districts are numerous — and many of the odd shapes in his plan are analogous to the PMC's (People's Maps Commission). For example, Governor Evers redrew Senate District 4, currently represented by Sen. Taylor, to extend into Waukesha and Ozaukee Counties. The result was a substantial decrease in BVAP (Black voting-age population). Under his plan, Assembly District 11 would extend to Mequon. In critiquing a similar feature of the PMC's map, Rep. LaKeshia Myers rhetorically asked, "[w]hy? That's going to cross the county line. Doesn't make sense. Doesn't make sense at all. . . . That's not going to stick when it comes to people's interest. That's not going to stick when it comes to thinking you're going to elect people that look like me." Without any VRA (Voting Rights Act)-grounded justification, Governor Evers violated Article IV, Section 4 the Wisconsin Construction, which requires assembly districts "to be bounded by county, . . . town, or ward lines[.]" Governor Evers' plan also would have harmed the Black community by forcing it to bear the brunt of disruption stemming from redistricting. While demonstrating high overall core retention, Governor Evers concentrated major changes in Milwaukee County, proposing what the Legislature fairly labelled a "most-change Milwaukee" map. According to the Legislature, Governor Evers' plan would have retained merely 72.6% of Milwaukee-area voters in their current district. In accordance with the principles expounded in our November 30 opinion, this court rightly rejects a "most-change Milwaukee," as the Legislature did with a bipartisan vote months ago. "State authorities" should not "localize the burdens of race reassignment" on a particular community. It leaves "the impression of unfairness" when a discrete and insular minority "disproportionately bears the adverse consequences of a race-assignment policy." This redistricting cycle proceeded in a manner heavily focused on color, supposedly for remedial purposes, but accomplishing nothing but racial animosity as showcased by the dissent's race-baiting rhetoric and condescension toward people of color. - Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Rebecca Grassl Bradley In contrast to Governor Evers' plan, the Legislature's plan does not engage in the systematic and discriminatory dismantling of districts in Milwaukee. Governor Evers would sever Black voters' existing constituent-representative relationships and undermine existing voter coalitions, while largely preserving them for White voters. Whether maximizing majority Black voting districts would actually benefit the Black community remains highly suspect. Had it survived the scrutiny of the United States Supreme Court, Governor Evers' plan arguably would have limited Black communities' political power. Senator Lena Taylor wrote an amicus brief to the United States Supreme Court explaining how Governor Evers' maps "dilute[] the voting strength of Black voters in Wisconsin." She continued, "the [Wisconsin] supreme court's conclusion – with no analysis whatsoever – that the Governor's map complies with the Voting Rights Act is clearly erroneous. ... It made no determination of whether the Governor's map – or any other – contains seven Assembly districts with an effective Black majority."

The Legislature has repeatedly told this court its maps are race neutral. No party presented any evidence to this court calling into question the Legislature's attorneys' compliance with their duty of candor, but the dissent nevertheless lodges the accusation. ***  Karofsky Karofsky Note: Hey, this one is a little different! WJI's "SCOW docket" pieces generally include decisions, dissents and concurrences all in one post. This time, with this case, we are doing it in three: First we shortcutted the decision, then the dissent, and next the concurrences. Why? Because this package of writings, and the strange U.S. Supreme Court decision that led to it, are extremely important to the state and country. Besides that, the SCOW decisions are unusually long – 142 pages, all in, not counting the cover sheets. And instead of allowing each writing justice 10 paragraphs, we are giving each 15. Other than that, the rules remain the same. We've removed citations from the opinion for ease of reading, but have linked to important cases cited or information about them. Italics indicate WJI insertions except for case names, which also are italicized. The case: Billie Johnson v. Wisconsin Elections Commission Dissent: Justice Jill J. Karofsky (39 pages), joined by Justices Ann Walsh Bradley and Rebecca F. Dallet Concurrence: Justice Rebecca Grassl Bradley (49 pages), joined by Justice Patience D. Roggensack and Chief Justice Annette K. Ziegler Concurrence: Justice Brian Hagedorn (4 pages) Majority opinion: Ziegler (50 pages), joined by Grassl Bradley, Hagedorn, and Roggensack (See part 1) Karofsky begins her dissent with a bit of background on the "odyssey" that led to SCOW's original decision to select redistricting maps submitted by Gov. Tony Evers. That decision was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which overturned it and sent it back to SCOW, which then selected maps submitted by the Legislature. We are careening over the waterfall because the Legislature's maps fare no better than the Governor's under the U.S. Supreme Court's rationale. If, according to the U.S. Supreme Court, the Governor's addition of a Milwaukee-area majority-minority district evinces a disqualifying consideration of race, then the Legislature's removal of a Milwaukee-area majority-minority district reveals an equally suspect, if not more egregious, sign of race-based line drawing. In addition, if a further-developed record is required to definitively determine whether the Governor's seventh majority Black district is required then a further-developed record is also required to definitively determine that the Legislature's removal of a majority-minority district does not violate federal law. The Court indicated that in a case like this where the court sits as the map-drawer in the first instance, the court, rather than the parties, are responsible for showing that the number of majority-minority districts required by the VRA (Voting Rights Act) constitutes the narrowly tailored remedy allowed under the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause. In choosing the Legislature's maps the majority repeats this court's reversible mistake by again failing to implement fact-finding procedures conducive to addressing the relevant issues under both the VRA and the Equal Protection Clause. *** Karofsky briefly traces Milwaukee's history of segregation and discrimination. The VRA's application in redistricting is designed to remedy precisely these kinds of historical wrongs – those that create current barriers to democratic participation. Instead of allowing the past unconstitutional practices of redlining and racially restrictive covenanting to continue limiting Black people's opportunity to participate in our democracy, the VRA establishes that it is a sufficiently compelling government interest to draw districts that counteract the historical racial gerrymander. We must, of course, also consider the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause. And in doing so, it is impossible to ignore the 180-degree turn from that clause's purpose to how it has been wielded in this case. Ratified in 1868 after the Civil War, the Fourteenth Amendment demands that no state shall "deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." Since Brown v. Board of Education, the Equal Protection Clause has been invoked to desegregate this country, protect the voting rights of its citizens, and fight discrimination in its many forms. More recently, the Equal Protection Clause has been turned on its head and used, not to fight against the constant pull of our collective historical failing toward the promise of a better future, but to bar our government's ability to remedy past mistakes. The majority opinion perfectly captures this reversal by relying on cases pontificating that "[r]acial gerrymandering, even for remedial purposes, may balkanize us into competing racial factions," and that "[r]ace-based assignments . . . embody stereotypes that treat individuals as the product of their race[.]" This argument is nothing short of gaslighting, seemingly denying Milwaukee's history of purposeful racial segregation. It was unrelenting overt racial discrimination that balkanized Milwaukee into "competing racial factions" and reduced Black individuals to a "product of their race." The fault and responsibility to remedy this systemic segregation lies not with Milwaukee's residents but instead with the government and the society that perpetuated racial redlining and restrictive covenants. Those practices shaped Milwaukee and that history of discrimination cannot be undone by force of will alone. The Milwaukee area perfectly demonstrates why the VRA's race-conscious remedy is often needed. Segregation of minority communities does not happen accidentally. If this country were anywhere close to living up to the "goal of a political system in which race no longer matters," then maybe we could apply the promise of Equal Protection in a race-blind manner. But the overwhelming evidence shows that we have not lived up to that goal. As such, a race-blind and effects-blind application of the Equal Protection Clause has become a sword against progress wielded by majority groups who fear giving away too much of their accumulated power. I fervently hope it will regain its place as a shield against harmful discriminatory action. *** Prior to the U.S. Supreme Court's decision, an Equal Protection analysis began with whether "race was the predominant factor motivating the [map-drawer]'s decision to place a significant number of voters within or without a particular district. That entails demonstrating that the [map-drawer] 'subordinated' other factors –compactness, respect for political subdivisions, partisan advantage, what have you – to 'racial considerations.'" Yet, the Court's opinion did not first analyze whether race was the "predominant factor" motivating this court's districting decisions. Instead, it appeared that the Court took this court's limited analysis regarding the VRA, meant only to ensure the least-change map did not violate that law, as evidence that race – not least change – predominated our choice of maps. Our March 3 opinion never professed as much. While the U.S. Supreme Court's opinion said it was unclear whether this court viewed itself or the Governor as the map-drawer, we plainly stated that the court itself was the map-drawer. ("As a map-drawer, we understand our duty is to determine whether there are 'good reasons' to believe the VRA requires a seven-district configuration.") *** Despite our clear declaration that "least change" predominated our choice of maps, and despite the purported purpose of "least change" as a neutral criterion to shed ourselves of the political baggage that would be inherent in party-drawn maps, the Court nonetheless transposed the Governor's motivations onto this court. We are left to conclude that the motivations of the party submitting the map are the relevant motivations we must analyze going forward. This court can no longer hide behind a "least change" gloss to ignore a party's ulterior motives. The U.S. Supreme Court left us with other unanswered questions:

In light of these uncertainties, and in order to avoid further reversible error, I believe we must implement one of the first three options set out above: (1) invite further briefing and fact finding on the unsettled VRA questions; (2) invite an expert or the parties to submit redrawn, race-neutral maps for the Milwaukee area; or (3) invite an expert or the parties to submit a whole new, reliably-race-neutral map. The majority opinion attempts to shift the blame by noting that the parties stipulated through their joint discovery plan that they did not anticipate discovery "beyond the exchange of maps, expert disclosures, and any documents or data that a party intends to rely upon or an expert has relied upon." But we had the authority, indeed the responsibility, to direct further discovery or examination of expert witnesses. This court's initial reliance on the joint discovery plan was guided by the court's "least change" directive, which failed to account for the full and definitive Equal Protection or VRA inquiry the U.S. Supreme Court now demands. This persistent imprudence in developing a record has now led us to a legally untenable outcome at odds with the Court's directive. The Equal Protection and VRA claims usually litigated after the implementation of a remedial map must now be fully adjudicated as part of this decision – an impossible task on this record. *** The Legislature's maps fail for two reasons: first, we are not to act as a gubernatorial veto override body; and second, the Legislature's maps show evidence of racially motivated packing and cracking that could violate both the Equal Protection Clause and the VRA. The Legislature's maps derive from a failed political process. In Wisconsin, the redistricting process follows the same process as the enactment of any law. Both houses of the legislature must pass a bill containing new maps, which is then presented to the governor who may approve or veto the bill, the latter of which the legislature may override with a supermajority vote. Here, the Legislature, having failed to override the gubernatorial veto, submitted the very same proposal to us. By now implementing that failed bill, this court judicially overrides the Governor's veto, thus nullifying the will of the Wisconsin voters who elected that governor into office. But our constitution provides only one avenue to override such a veto; no judicial override textually exists. Nor, historically, has this court ever exercised such a supreme power. By judicially enacting the very bill that failed the political process, a bare majority of this court, rather than a supermajority of the legislature, has taken the unprecedented step of removing the process of lawmaking from its constitutional confines and overriding a governor's veto ourselves. More recently, the Equal Protection Clause has been turned on its head and used, not to fight against the constant pull of our collective historical failing toward the promise of a better future, but to bar our government's ability to remedy past mistakes. - Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Jill J. Karofsky In addition to being derived from a failed political process, the Legislature's maps show signs of violating the Equal Protection Clause. If, as the U.S. Supreme Court explained, the Governor's addition of a majority-minority district sufficed to show that race predominated its proposal, then equally, if not more, suspect is the Legislature's removal of a majority-minority district. Despite the majority opinion's assertions, the Legislature's maps do not appear to be race-neutral and calling the claim "indisputable" does not make it so. The Legislature's claim that it drew its maps without considering race, quite frankly, flies in the face of its transfiguration of Milwaukee's six current districts with a Black voting age population (BVAP) majority. In Milwaukee, the BVAP increased 5.5 percent while the White voting age population decreased 9.5 percent over the last decade. Those demographic changes make the Legislature's draw down of BVAP percentage in five out of six VRA districts – one by over 12 percent – with the remaining VRA district packed at 73.3 percent BVAP highly suspicious.

*** Self-serving professions of race-neutrality should also be ignored because the Legislature offered no alternative reasons for making decisions regarding Milwaukee's districts. The Legislature's "least change" pretext fails when it openly admits its Milwaukee-area changes substantially differed from its treatment of the rest of the state. Nor can the Legislature justify its unique redrawing of Milwaukee districts on a desire to keep municipalities whole; it split at least one relevant village, Brown Deer, by dividing its Black population between two districts. Respecting "communities of interest" also fails to justify the Legislature's actions because no party submitted evidence establishing such communities. That leaves the more nefarious partisan advantage reasoning – a reliable pretext for racial motivations. But a neutral judicial body cannot adopt a map on such a justification, especially now that the party's motives are imputed onto the court. The Legislature also has not, and could not, claim such a justification as this court barred consideration of partisanship in our redistricting process. As such, no judicially acceptable justification for the Legislature's Milwaukee-area redistricting decisions exists. *** This has been a profoundly disheartening odyssey. The unavoidable political nature of remedial redistricting plagued us every step of the way. Too rarely did this process present true questions of law – this court's only area of expertise. At every change in the tide, this court seemed to choose what it hoped to be a short-cut to streamline our voyage, only to find ourselves lost and unable to do our work as a non-partisan court of law. But the redistricting process is likely to stalemate and come before this court again in the future. And when it does, I hope that we have learned our lesson. I hope that we will permit a politically insulated federal court to manage the task. Federal courts are better able to conduct extensive factfinding through trial-style litigation, a task for which we proved ill equipped. Note: Hey, this one is a little different! WJI's "SCOW docket" pieces generally include decisions, dissents and concurrences all in one post. This time, with this case, we are doing it in three: First the decision, then the dissent, then the concurrences. Why? Because this package of writings, and the strange U.S. Supreme Court decision that led to it, are extremely important to the state and country. Besides that, the SCOW decisions are unusually long – 142 pages, all in, not counting the cover sheets. And instead of allowing each writing justice 10 paragraphs, we are giving each 15. Other than that, the rules remain the same. The "upshot" and "background" sections do not count as part of the 15 paragraphs because of their summary and very necessary nature. We've also removed citations from the opinion for ease of reading, but have linked to important cases cited or information about them. Italics indicate WJI insertions except for case names, which also are italicized. The case: Billie Johnson v. Wisconsin Elections Commission Majority opinion: Justice Annette K. Ziegler (50 pages), joined by Justices Rebecca Grassl Bradley, Brian Hagedorn, and Patience Roggensack Concurrence: Grassl Bradley (49 pages), joined by Roggensack and Ziegler Concurrence: Hagedorn (4 pages) Dissent: Justice Jill J. Karofsky (39 pages), joined by Justices Ann Walsh Bradley and Rebecca F. Dallet  Ziegler Ziegler The upshot Upon review of the record, we conclude that insufficient evidence is presented to justify drawing state legislative districts on the basis of race. The maps proposed by the Governor, Senator Janet Bewley, Black Leaders Organizing for Communities ("BLOC"), and Citizen Mathematicians and Scientists ("CMS") are racially motivated and, under the Equal Protection Clause, they fail strict scrutiny. By contrast, the maps proposed by the Wisconsin Legislature are race neutral. The Legislature's maps comply with the Equal Protection Clause, along with all other applicable federal and state legal requirements. Further, the Legislature's maps exhibit minimal changes to the existing maps, in accordance with the least change approach we adopted in Johnson v. Wis. Elections Comm'n. Therefore, we adopt the state senate and assembly maps proposed by the Legislature for the State of Wisconsin. Background In 2011, the Wisconsin Legislature passed and the Governor signed state legislative and congressional maps after the 2010 census. Over the subsequent ten years, the population of Wisconsin changed; people moved away from some areas and people moved into others. These changes were recognized in the 2020 census, which identified a population increase in the state from 5,686,986 to 5,893,718. The Petitioners filed this original action in August 2021 to remedy alleged malapportionment in Wisconsin's state legislative and congressional maps. In September 2021, this court accepted the case, and in October 2021, the court directed the parties to file briefs addressing what factors the court should consider when selecting new maps. ... On November 30, 2021, the court issued a decision explaining the framework by which the court would select maps. The court identified that under the Equal Protection Clause of the United States Constitution, "a State [must] make an honest and good faith effort to construct districts, in both houses of its legislature, as nearly of equal population as practicable...." The court explained that, in addition to satisfying all Equal Protection Clause requirements, the court must consider compliance with Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act ("VRA"). ... In its November 30 decision, the court adopted the "least change approach," whereby the court would select maps that "comport with relevant legal requirements" while "reflect[ing] the least change necessary." The court rejected the suggestion that the court consider partisan fairness and proportional representation of political parties when selecting maps. *** On March 3, 2022, the court issued a decision adopting the Governor's state legislative and congressional maps. The court reasoned that the Governor's maps included the least alterations to preexisting maps. In addition, the court said that the Governor's maps complied with the Equal Protection Clause, the VRA, and the Wisconsin Constitution. After the court issued its March 3 decision, the Petitioners and the Legislature sought certiorari review by the United States Supreme Court, asserting that the court's adoption of the Governor's state legislative maps constituted a racial gerrymander in violation of the Equal Protection Clause. ... On March 23, 2022, the United States Supreme Court reversed the court's decision to select the Governor's state legislative maps. The Supreme Court confirmed that, under the Equal Protection Clause, a state government cannot draw district maps on the basis of race unless the state satisfies strict scrutiny. However, the state must possess this evidence before it creates maps based on racial classifications. In the case before this court, the Supreme Court reasoned that, based on the filings and presentations made by the Governor, the Governor had failed to present a strong evidentiary basis for believing the VRA mandated the district lines he drew. Specifically, the Supreme Court identified that the Governor's primary explanation for his racially drawn maps was the fact that it was cartographically possible to draw them. According to the Supreme Court, "[s]trict scrutiny requires much more." Based on the record, the Governor's maps failed to satisfy this legal standard. ... The Supreme Court remanded the case to us for further proceedings. The Court explained that we could "choose from among...other submissions." Alternatively, the court could "take additional evidence if [we] prefer[ed] to reconsider the Governor's maps." It instructed, however, that "[a]ny new analysis...must comply with our equal protection jurisprudence." *** The Supreme Court has demanded that three specific preconditions be met before it can conclude that the creation of additional majority-minority districts may be necessary: "(1) the racial group is sufficiently large and geographically compact to constitute a majority in a single-member district; (2) the racial group is politically cohesive; and (3) the majority vote[s] sufficiently as a bloc to enable it . . . usually to defeat the minority's preferred candidate." These three requirements are called the "Gingles preconditions." ... The VRA requires an "intensely local appraisal" which "pars[es] . . . data at the district level" and evidences a lack of minority electoral opportunity, such that a race-based remedy is needed. ...The inquiry is emphatically not to create "the maximum number of majority-minority districts," regardless of the on-the-ground characteristics of the minority communities under consideration. ... The guts